TLDR: When extremists seized Timbuktu in 2012 and began burning shrines and manuscripts, local librarians and residents quietly mounted a low-tech resistance: they smuggled some 300,000 medieval African texts—on astronomy, medicine, law, poetry, and more—out of the city by donkey cart, motorcycle, canoe, and car, outwitting Al-Qaida with metal trunks and neighborhood trust. Those same manuscripts, long stored in humid, makeshift conditions in Bamako and increasingly digitized with international help, are now slowly flying back home: 28,000 returned to Timbuktu in 2025, to climate-controlled vaults in the city that created them. The story isn’t a neat victory lap but an ongoing gamble in a still-unstable region, where the real power struggle isn’t just over territory but over who gets to define history, faith, and knowledge—and where the most consequential actors turned out to be the people with keys to the archives, not the guns.

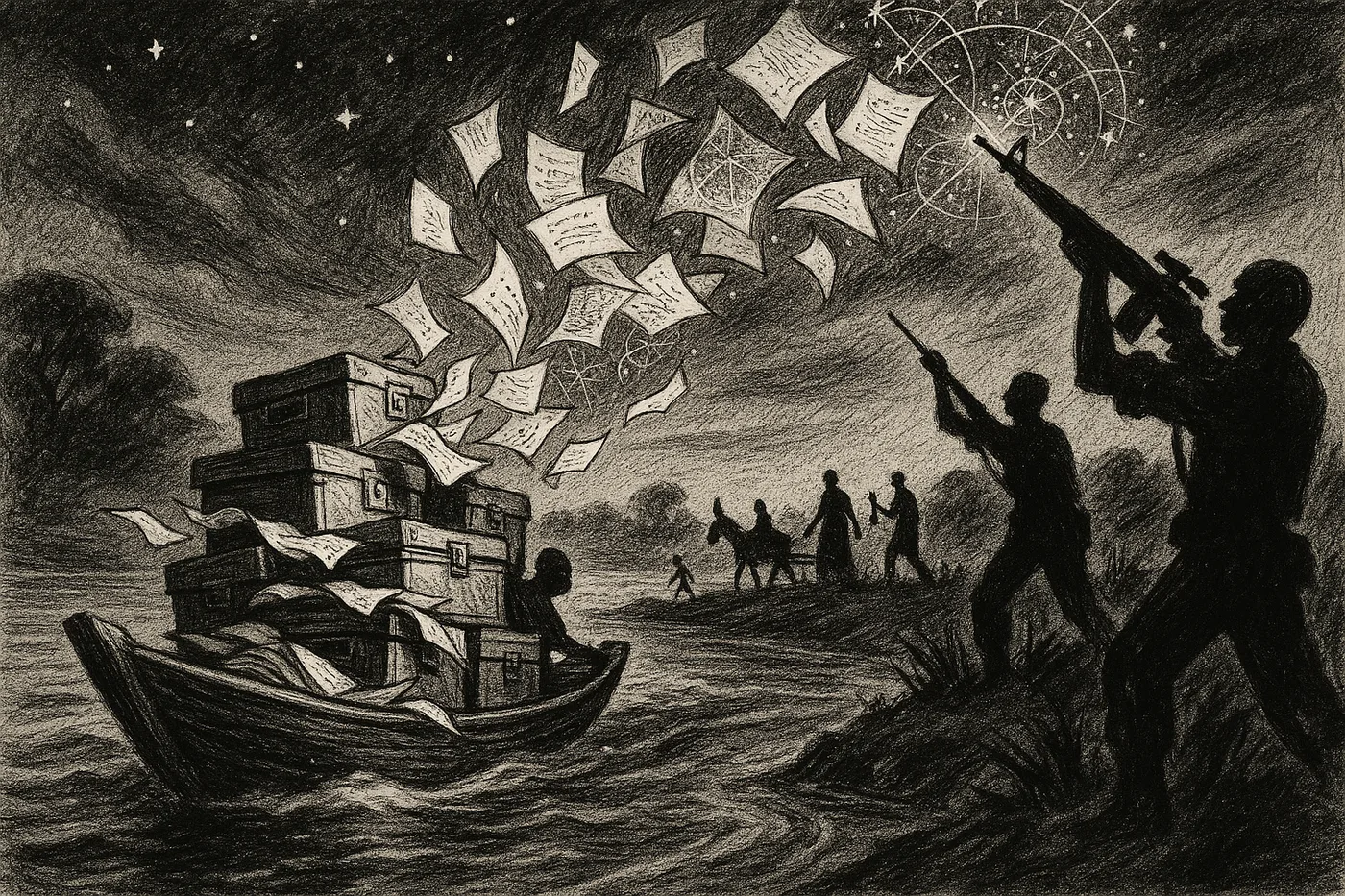

On a summer night in 2012, a wooden boat slid down the Niger River, piled high with metal trunks. Armed forces spotted it and raised their weapons.

Guns? Explosives?

The "contraband" inside those trunks was something Al-Qaida considered just as dangerous: books.

Centuries-old Timbuktu manuscripts filled the boat—handwritten texts on astronomy, medicine, law, poetry, star charts, even spells. The people aboard weren't warlords. They were librarians and neighbors trying to outrun an ideology with nothing but donkey carts, canoes, and an obsessive respect for paper.

Which raises a question: why would ordinary people risk their lives for "old texts"—and why are 28,000 of them flying back home in 2025?

This isn't just a story about extremists burning books. It's about medieval African scholarship, cultural heritage as resistance, and what happens when the most powerful people in town turn out to be the ones with keys to the archives.

What Was At Stake

Timbuktu isn't a metaphor for "middle of nowhere." For centuries, it anchored one of the world's major centers of Islamic learning—a desert crossroads where scholars debated astronomy, medicine, and governance while Europe stumbled through its own Middle Ages.

The Timbuktu manuscripts number somewhere between 400,000 and 700,000 handwritten pages, produced from the late 13th century into the early 20th. Most are in Arabic, with African languages like Songhai and Fulfulde written in Arabic script.

In 2012, that legacy collided with force. Al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb and Ansar Dine seized Timbuktu amid Mali's political crisis, imposed hardline rule, and demolished nine mausoleums and a mosque door—all UNESCO World Heritage sites. They burned or stole over 4,000 manuscripts at the Ahmed Baba Institute.

What they couldn't torch, locals quietly moved.

Between June 2012 and January 2013, librarians and residents smuggled roughly 285,000 to 350,000 manuscripts—about 95% of the known collection—over 700 kilometers to Bamako, Mali's capital.

Thirteen years later, the first manuscripts have begun the journey home.

The Night Librarians Who Outwitted Al-Qaida

Abdel Kader Haidara, director of the Mamma Haidara library and descendant of a scholarly family, grasped the danger early. He'd spent decades trekking across the Sahara, persuading families to bring their private manuscript collections into safer storage.

Now he had to reverse course: get the books out.

With the NGO SAVAMA-DCI, Haidara and colleagues like Abdoulaye Cissé orchestrated what amounted to a slow-motion heist.

Night after night, they packed manuscripts into 2,400 metal chests. Donkey carts ferried trunks through dark streets to safe houses. Families hid manuscripts in their homes. When routes cleared, the boxes moved again—into rice sacks, onto motorcycles and jeeps disguised as fruit transporters, onto pirogues slipping down the Niger.

The operation required:

- Roughly 1,200 individual car journeys

- Hundreds of thousands of fragile pages

- Constantly changing routes to dodge checkpoints

- Initial funding from personal savings

At one point, French forces intercepted a boat full of manuscripts, mistaking them for weapons. They nearly opened fire before confirming the cargo was old paper.

It was the most low-tech operation Al-Qaida never anticipated. While extremists staged spectacles of power, the most subversive act in Timbuktu was a librarian with a network of neighbors who refused to let their past be edited by men with guns.

Inside The "Dangerous" Texts

The Timbuktu manuscripts aren't just Qurans on old paper. They're a sprawling record of medieval African intellectual life.

Among them:

Astronomy and mathematics

Star charts tracking eclipses and planetary movements, advanced equations, celestial calendars. The Sahara was producing sophisticated astronomical work while its scholars debated the movements of the cosmos.

Medicine and herbal science

Diagnoses, herbal remedies, treatment protocols. One modern Timbuktu medical student now studies these texts, hoping to help patients who can't afford imported drugs.

Law, theology, and ethics

Centuries of arguments over Islamic jurisprudence, governance, and morality. Not slogans—debates about how to run a just society.

History and philosophy

Chronicles of the Mali and Songhai empires, biographies of scholars, reflections on knowledge and power.

Poetry, Sufism, and the occult

Love poems, mystical writings, plus geomancy, astrology, and spell collections. These texts show an Islam far more nuanced than the rigid version extremists promote.

As Haidara puts it: people say Africa's history is only oral. These hundreds of thousands of manuscripts say otherwise.

They prove medieval African cities like Timbuktu, anchored by institutions like the University of Sankore, were nodes in a global network of serious scholarship.

If you're selling a narrow vision of religion and power, centuries of written debate are inconvenient.

When Cultural Destruction Backfires

Ansar Dine and AQIM didn't just burn texts—they attempted to erase who gets to define Islam and history in northern Mali.

Destroying manuscripts, mausoleums, and Timbuktu's "sacred gate" followed a classic pattern: erase alternative practices and memories, and you shrink people's sense of what's possible.

It looked like strength. But it triggered consequences that outlast the militants.

The manuscripts escaped. In 2016, Ansar Dine leader Ahmad al-Faqi al-Mahdi was convicted by the International Criminal Court for directing the destruction of Timbuktu's mausoleums—the ICC's first case treating cultural heritage destruction as a war crime.

UNESCO and Mali's government responded not with silence but with action: rebuilding mausoleums using traditional methods, expanding preservation programs, reviving scholarship, broadening access.

For groups obsessed with domination, the most dangerous opponents in Timbuktu weren't the ones with weapons. They were the ones with catalogues, keys, and very long memories.

From Fire To Humidity

Surviving extremists was only the first test.

In Bamako, the manuscripts faced a quieter threat: climate. Timbuktu's dry desert air had preserved paper for centuries. Bamako is humid. Stored in trunks and improvised rooms, manuscripts molded and warped.

SAVAMA-DCI organized cleaning, restoration, and better storage. A crowdfunding campaign called "Timbuktu Libraries in Exile" funded climate-controlled spaces. International partners—the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library, the University of Hamburg's Centre for the Study of Manuscript Cultures, UNESCO, ICESCO—provided digitization support.

Before 2012, only 20% of the Ahmed Baba collection had been digitized. Since then, over 150,000 manuscripts have been photographed and catalogued, creating a digital safety net.

But as one conservator noted, manuscripts locked in trunks remain "dead"—people can't study or enjoy them. Protection without access is just another kind of loss.

Humidity became the final argument for a move that sounded risky: sending manuscripts back into the region they'd fled.

The Flight Home

In August 2025, Mali's military-led transitional government flew crates of Timbuktu manuscripts north, responding to requests from local leaders and civil society.

Around 28,000 texts landed in Timbuktu after 13 years. They're now housed at the Ahmed Baba Institute in climate-controlled conditions—a small fraction of the total collection, but symbolically enormous.

Higher Education Minister Bouréma Kansaye calls them "a bridge between the past and the future." Timbuktu's deputy mayor describes them as reflections of the city's civilization and intellectual heritage.

But this isn't the end of the story. Roughly 300,000 manuscripts remain in Bamako, where security is more predictable despite worse climate. Northern Mali remains volatile—Al-Qaida-linked fighters attacked near Timbuktu in June 2025, and armed groups have imposed fuel blockades that complicate preservation work.

The repatriation is less a happy ending than a calculated bet: these texts are safer, and more alive, in the city that produced them—even if the region remains unstable.

What The Librarians Are Really Saying

The real contrast here cuts deeper than "terrorists versus ruins."

On one side: militants chasing quick domination through fear and destruction. On the other: librarians, families, drivers, and students playing the long game—deciding what knowledge survives and who gets to use it.

Heroism looks like:

- Persuading families to entrust manuscripts they've guarded for generations

- Packing metal chests on sweltering nights and navigating checkpoints

- Students in 2025 hunched over scanners, turning fragile pages into pixels

- Local leaders insisting manuscripts belong in Timbuktu, not distant storage facilities

The threats shifted, too. After the cameras left, the biggest dangers became humidity, funding gaps, and the slow erasure that comes when no one reads or teaches the texts.

Timbuktu's response: reopen exhibitions, train conservators, plug medieval manuscripts into a modern global network of researchers and curious readers.

You can see it yourself—digitized Timbuktu manuscripts are online, and books like The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu and The Book Smugglers of Timbuktu tell the inside story.

From Donkey Carts To Data Clouds

In 2012, manuscripts left Timbuktu in rice sacks on donkey carts and creaking boats, chased by armed militants.

In 2025, those same texts flew home by plane, backed up in digital archives, housed in climate-controlled vaults. They're not invincible—nothing on paper ever is. But they're much harder to erase than the night a nervous boat crew drifted past armed forces.

Maybe that's the strangest twist. In a city once dismissed as the far edge of the map, the most radical act in a war zone wasn't picking up a gun.

It was picking up a book, refusing to let it burn, and making sure centuries later, you could read it too.