TLDR: Egypt has quietly ended a 3,500‑year battle with trachoma—not by miracle cure, but through two decades of unglamorous public health work that turned face‑washing at a rural school tap into a frontline defense against blindness. By combining the SAFE strategy (surgery, antibiotics, hygiene, and environmental improvements) with massive rural infrastructure upgrades under the Haya Karima initiative, Egypt drove active trachoma in children below 2% and blinding complications in adults below 0.2%, earning WHO validation in November 2025. This is less a story about a single breakthrough than a blueprint for how boring-but-reliable systems, clean water, community-led behavior change, and patient surveillance can retire an ancient disease. In a world still leaving 103 million people at risk of trachoma, Egypt’s victory offers a non‑Western model of what it takes to turn “inevitable” suffering into a preventable footnote.

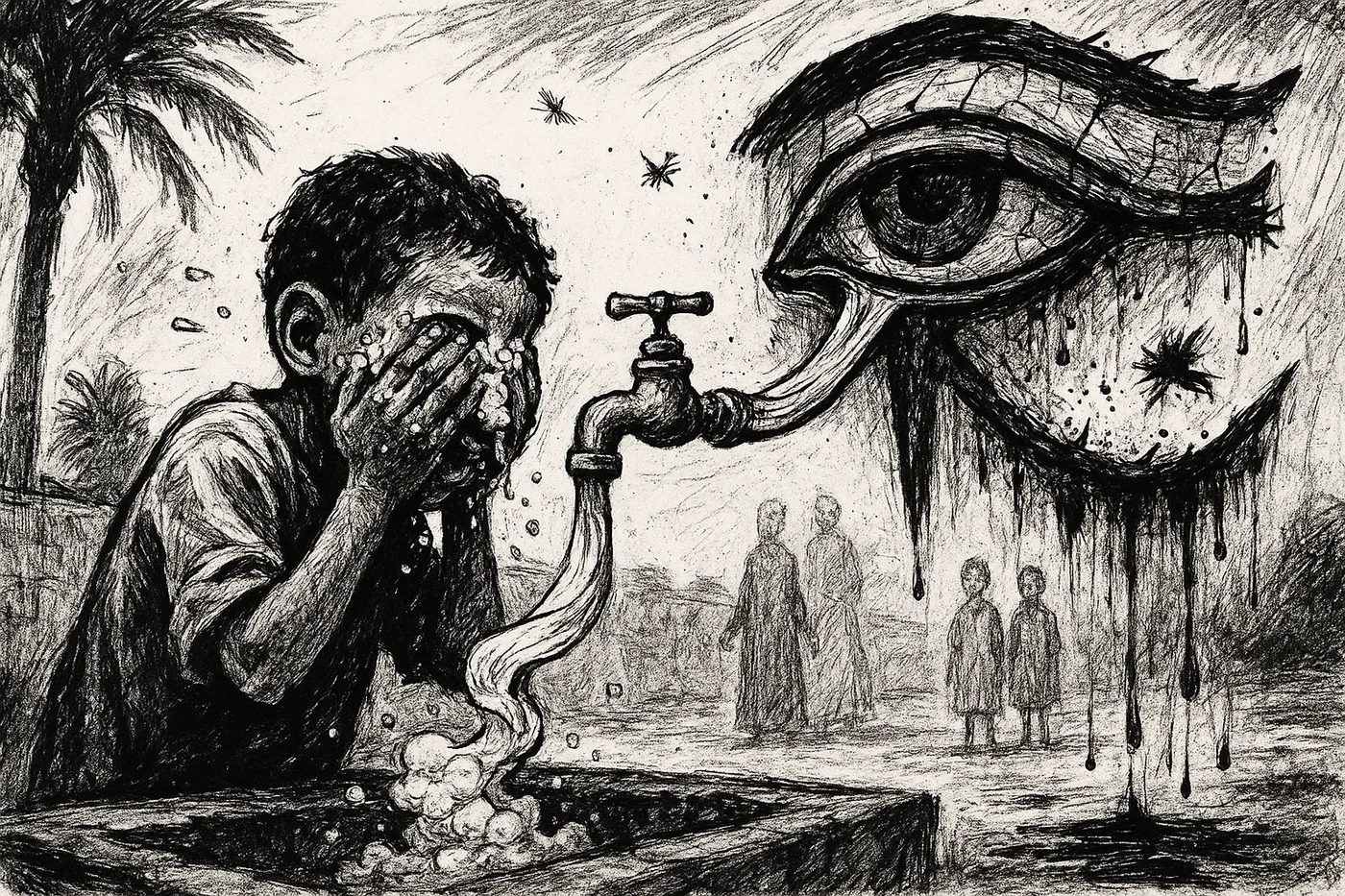

Picture a child in rural Upper Egypt lining up at school to wash their face at a tap before class. Water, soap, a teacher reminding them to scrub properly. Nothing remarkable.

Except this: that small, unglamorous act helped end a disease first documented by ancient Egyptian physicians around 1550 BCE.

On November 12, 2025, the World Health Organization confirmed Egypt's elimination of trachoma as a public health problem—a blinding eye infection that has plagued humanity since before the pyramids of Giza cast their first shadows. Egypt becomes the seventh country in the WHO's Eastern Mediterranean Region and the twenty-seventh globally to reach this milestone.

This isn't a miracle-cure story. It's a two-decade grind involving the SAFE strategy, rural infrastructure through the Haya Karima initiative, and a surveillance system that makes spreadsheets look exciting. And that's exactly what makes it worth understanding.

We'll track the arc from papyrus scrolls to electronic disease monitoring, examine how rural communities carried the heaviest load, and question why some global health victories make headlines while others barely register.

Welcome to one of the quietest public health triumphs of our time.

What Trachoma Actually Does

Trachoma operates with brutal simplicity.

The bacterium Chlamydia trachomatis spreads through infected eye discharge transferred by unwashed hands, shared fabric, contaminated surfaces, and flies drawn to crowded spaces with poor sanitation. Children catch it most easily, but the worst damage appears decades later.

Each infection scars the inside of the eyelid. Eventually, the eyelashes flip inward—a stage called trachomatous trichiasis—and scrape the cornea with every blink. Imagine fine sandpaper dragging across your eye all day, every day, until vision slowly dims, then disappears. No dramatic outbreak. Just sight methodically stolen from the same families, generation after generation.

Egypt has lived with this disease for over three millennia. It persisted in Nile Delta villages and rural communities starved of clean water well into the 20th century. Ophthalmologist Arthur Ferguson MacCallan established Egypt's first mobile and permanent eye hospitals in the early 1900s, pioneering organized trachoma control globally. Yet by century's end, the disease still blinded thousands annually.

Worldwide, trachoma remains active. As of April 2025, it causes blindness or visual impairment in approximately 1.9 million people and threatens another 103 million. Against that backdrop, Egypt's WHO verification carries weight: more than two million Egyptians no longer face the risk of losing their sight to this ancient scourge.

From Papyrus Remedies to Modern Elimination

To grasp the strangeness of Egypt's achievement, rewind to 1550 BCE.

The Ebers Papyrus, one of the oldest preserved medical texts, describes advanced trachoma and prescribes treatments. Ancient physicians crafted ointments from myrrh, honey, and malachite. Some recipes incorporated lizard and bat blood. They performed crude eyelash removal for trichiasis.

These weren't superstitions. They were serious medical interventions attempted in a world without microscopes, antibiotics, or germ theory. Judging them misses the point—what matters is the contrast.

Then: papyrus scrolls and myrrh-based ointments.

Now: surgery, mass antibiotic distribution, hygiene education, rural water infrastructure, and WHO validation.

Same disease. Entirely different tools.

The Unglamorous Strategy That Worked

Egypt deployed the WHO-endorsed SAFE strategy starting in 2002, following a 2001 pilot:

Surgery for people already at the blinding stage (trichiasis).

Antibiotics, primarily azithromycin through mass drug administration campaigns.

Facial cleanliness, especially among children, to disrupt person-to-person transmission.

Environmental improvement: clean water access, sanitation facilities, reduced household crowding, fly control.

The Ministry of Health and Population coordinated with WHO and partners including Sightsavers, CBM, the International Trachoma Initiative, Haya Karima Foundation, and Egyptian organizations like the Nourseen Charity Foundation and Magrabi Foundation.

Between 2015 and 2025, teams conducted mapping and surveillance across all 27 governorates, repeatedly examining children aged 1–9 and tracking adult complications.

The numbers tell the story:

Active trachoma in children dropped below the WHO threshold of 2% nationwide.

Trichiasis in adults fell below 0.2%, with surgical services available where needed.

Mass drug administration with donated azithromycin expanded in endemic areas like Al Minya starting in 2019, replacing earlier topical antibiotics and accelerating infection decline.

No breakthrough moment. Just consistent data collection, community outreach, and clinical work repeated until the disease curve bent downward. That grinding accumulation of evidence allowed WHO to certify elimination on November 12, 2025.

Rural Infrastructure: The Invisible Foundation

You cannot wash a child's face without water.

The Haya Karima initiative quietly enabled much of SAFE's facial cleanliness and environmental components. This massive rural development program expanded access to safe water, sanitation systems, and primary healthcare in villages that had endured trachoma for centuries.

Consider what changed:

Communities dependent on shared canals received household water taps.

Families built latrines, eliminating open defecation and fly breeding sites.

Clinics trained nurses to explain that keeping children's faces clean protects their eyesight as much as textbooks protect their education.

Schools established morning routines where face-washing became as ordinary as taking attendance.

These weren't charity projects. They represented structural transformation. When WHO leaders cite Haya Karima as "transformative," they mean rural communities gained the infrastructure that ancient diseases require to maintain their foothold.

The benefits extend beyond trachoma. Clean water and working sanitation reduce diarrheal disease, improve maternal health, and restore dignity. Eliminating trachoma becomes the visible marker of deeper change.

What Elimination Actually Means

Precision matters here: Egypt eliminated trachoma as a public health problem. It did not eradicate the bacterium from existence.

Elimination in this context means the disease exists at levels too low to constitute a major public health threat, with systems positioned to detect and treat new cases rapidly.

Eradication would mean permanent global extinction—the status achieved only by smallpox.

WHO validation required Egypt to meet and sustain two thresholds:

Less than 2% of children aged 1–9 with active trachoma in every district.

Less than 0.2% of adults with trichiasis, with access to corrective surgery.

This wasn't based on a single survey. It rested on a decade of sustained surveillance across all governorates.

In 2024, Egypt integrated trachoma monitoring into its national electronic disease reporting system, enabling real-time case flagging and response. A disease first recorded in ink on papyrus now appears on digital dashboards.

The November 12 announcement at a global health conference near Cairo made it official: Egypt joined Iraq, Morocco, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Togo, and the United Arab Emirates as the seventh Eastern Mediterranean nation to reach this target.

Behind the ceremony sat twenty years of methodical work.

The People Who Made It Real

Their names don't appear in WHO documents, but their fingerprints cover every page.

A paramedic trained in trichiasis surgery watches the clinic waiting room steadily empty. Pride comes from mastering a sight-saving procedure. Satisfaction comes from needing that skill less each year because the disease itself is vanishing.

A teacher leading hygiene lessons tells students, "We wash our faces to protect our eyes." A child who once missed school with painful infections now stands first in line at the tap, eyes clear, arguing about homework instead of rubbing inflamed lids.

A village committee member helps maintain a new water system installed through Haya Karima, ensuring every household understands why latrines prevent disease. The shift runs deeper than plumbing: from accepting illness as fate to recognizing it as preventable through collective action.

These aren't victims requiring rescue. They're architects of the outcome.

Egypt's Place in the Global Picture

Egypt's success exists within a larger transformation.

Twenty-seven countries have now eliminated trachoma as a public health problem. The global at-risk population has plummeted from roughly 1.5 billion in 2002 to approximately 103 million in 2025—a 93% reduction.

Yet trachoma remains endemic in thirty countries, concentrated in communities facing extreme poverty, conflict, or fragile health systems. Funding cuts and crises can stall or reverse progress within years.

Egypt's achievement matters for two reasons:

First, it demonstrates a non-Western template for public health success. This marks the country's second neglected tropical disease elimination, following lymphatic filariasis in 2018.

Second, it validates the power of aligned partnerships. From Sightsavers and CBM to the International Trachoma Initiative, Haya Karima, and thousands of local health workers, the effort succeeded through coordination around national leadership and community engagement.

No savior narrative. No single hero. Just many actors pulling together long enough to bend the curve.

What Defeating an Ancient Disease Actually Requires

Strip away the medical terminology and Egypt's trachoma elimination becomes a study in sustained commitment overcoming historical inertia.

On one end: the Ebers Papyrus, where physicians documented eye diseases and prescribed myrrh, malachite, and lizard blood to ease trachoma's pain.

On the other: WHO verification that active trachoma in Egyptian children has fallen below 2%, trichiasis in adults sits below 0.2%, and surveillance systems now track potential cases electronically.

The gap closed not through miraculous breakthroughs but through:

Systems that function even when they're boring.

Rural health infrastructure that treats people as partners, not statistics.

The patience to count cases year after year until prevalence drops.

The conviction that an ancient scourge doesn't have to define modern lives.

When news cycles overflow with crisis and failure, quiet victories risk disappearing precisely because they aren't loud. Yet they prove that long-term investment in people, infrastructure, and unglamorous fundamentals can retire even diseases that have plagued humanity for thirty-five centuries.

The real measure of global health success isn't the conference photo or the press release. It's that child at the school tap, washing their face, never knowing they're part of the reason an ancient plague finally ran out of road.