TLDR: A £11,000-a-night Courchevel ski hotel burned overnight because its architecture—wooden attics, overlapping roofs, and snow-covered tiles—turned it into a fire trap, exposing systemic safety risks across alpine luxury resorts.

Option A: When a £11,000 Hotel Room Becomes a 15-Hour Fire Trap

Option B: The Courchevel Fire Wasn't Just Bad Luck—Alpine Luxury Is Built to Burn

Option C: Inside the Hidden Architecture That Turned a Ski Hotel Into an Inferno

Deck: A wooden attic, overlapping roofs, and a meter of snow turned a five-star hotel fire into a night-long battle—and exposed a problem across alpine resorts.

TL;DR: The Hotel Les Grandes Alpes fire spread so fast not because of what sparked it, but how the building was assembled—wooden voids, continuous roofs, and snow-laden tiles created conditions firefighters couldn't quickly access, revealing systemic risks in clustered alpine architecture.

Just before 7 p.m. on January 28, thick black smoke climbed into the twilight above Courchevel 1850, the world's most exclusive ski resort (Reuters, Jan 28). At the center stood Hotel Les Grandes Alpes, where peak-season rooms command over £11,000 per night. Within hours, 83 guests and staff evacuated into municipal blankets while more than 110 firefighters from three departments battled flames that refused to quit (France24, Jan 28; Franceinfo, Jan 28).

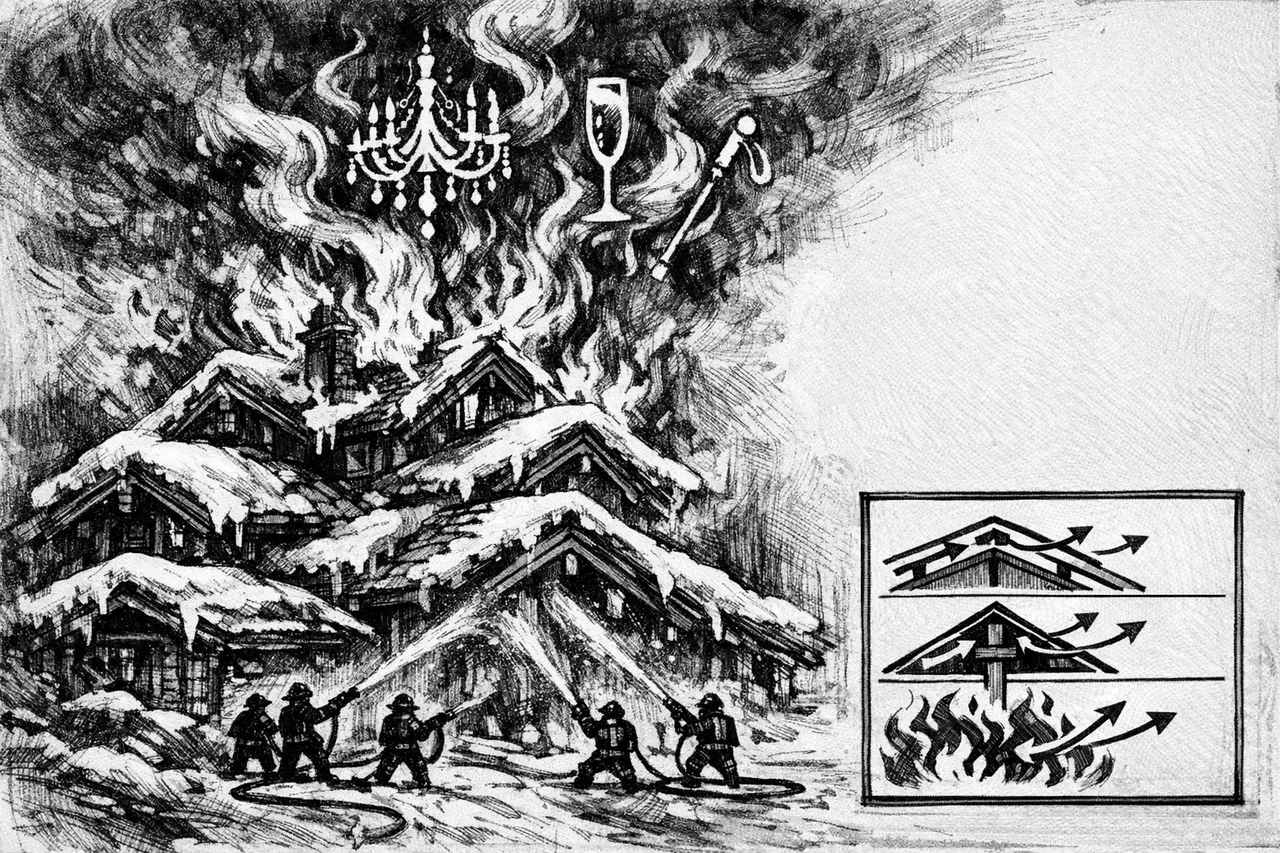

The blaze didn't stop until morning—and the question wasn't just what started it, but why it became unstoppable. The answer lies in the very architecture that defines alpine luxury: massive wooden chalets pressed together, roofs overlapping, attics forming superhighways for flame.

Courchevel's Billionaire Makeover—And the Density It Bought

Courchevel started in 1946 as architect Laurent Chappis's modernist experiment, carving France's first purpose-built ski resort into the Alps. By the 1970s, it had merged into the Trois Vallées domain and evolved into a billionaire haven boasting Europe's highest concentration of five-star hotels—where David Beckham rubs shoulders with Russian oligarchs and British royalty (Wikipedia; Euronews, Jan 28).

That density creates intimacy and risk. At Les Grandes Alpes, the roofline practically touches neighboring Hotel Le Lana, whose nearly 200 guests were evacuated as fire threatened to jump between buildings (Le Monde, Jan 28). "The buildings are contiguous, the chalets are gigantic and wooden," Courchevel mayor Jean-Yves Pachod told reporters. "It complicates the operation considerably" (Le Figaro, Jan 27).

The Roof Is the Battlefield: How Alpine Luxury Traps Fire

Investigators haven't identified the ignition source—the gendarmerie of Moûtiers opened an inquiry—but the structural conditions that amplified the fire are documented in official accounts (Le Parisien, Jan 28).

First, the attic voids. The fire started "in the attic of the Hotel des Grandes Alpes," according to prefecture officials (Reuters, Jan 28). Alpine chalets often feature unpartitioned wooden attic spaces with no fire stops between rooms or adjacent buildings. Once flame enters, it races along timber beams.

Second, the wooden core. Traditional timber framing—the charpente—acts as both fuel and ductwork, channeling heat and embers upward (Le Figaro, Jan 27). In luxury chalets, exposed beams are a selling point; in fires, they're a transmission system.

Third, overlapping roofs. Colonel Fabrice Terrien, director of the Savoie fire service, explained crews had to dismantle stone-tile roofing under heavy snow to access hidden flames (Euronews, Jan 28). That's because Courchevel's luxury core features "gigantic wooden chalets whose terraces and roofs intertwine," as Le Monde described it (Jan 28). Fire doesn't respect property lines.

Fourth, the snow load. Prefect Vanina Nicoli noted snow created "additional weight and thickness," blocking smoke vents and forcing firefighters to shovel before they could spray (France Bleu, Jan 28). Slate tiles prized for alpine authenticity became frozen lids trapping heat below.

By morning, over 1,000 square meters of roof were involved (Franceinfo, Jan 28). The fire wasn't declared circumscribed until late afternoon January 28, with residual hot spots lingering into the 29th (Libération, Jan 28; France Bleu, Jan 29).

The Night's Timeline

January 28, ~7 p.m.: Fire reported in attic; 83 guests and staff evacuate to municipal hall

Midnight: Prefecture warns intervention "will be long" due to roof construction

January 28, morning: Flames spread toward adjacent buildings; Hotel Le Lana evacuates ~190 people

10:30 a.m.: Prefect Vanina Nicoli: 110 firefighters working in "very difficult conditions" (Reuters, Jan 28)

Afternoon: Fire circumscribed but not extinguished; six firefighters suffer minor injuries—smoke inhalation, ankle sprains (Libération, Jan 28)

January 29: Investigation continues as crews monitor residual hot spots

The Ownership Question

Public records for Les Grandes Alpes ownership remain scarce. One outlet, citing Ukrainian publication Strana, alleged the hotel belonged to French companies linked to investment firm founder Igor Mazepa and partner Sergey Marfoot (EADaily, Jan 29). This claim is single-source and unverified—no major French outlets have corroborated ownership details.

What's confirmed: the building had been "recently inspected" with "no problems" found, according to Prefect Nicoli (France Bleu, Jan 28). But with nightly rates topping £11,000, the tension between preserving rustic charm and funding modern fire suppression remains acute.

Retrofits, Heritage, and the Price of Tradition

Renovating wooden alpine structures for fire safety is neither cheap nor simple. Research from Headwaters Economics indicates heritage timber retrofits can range from $2,000–$15,000 for basic upgrades like ember-resistant vents to nearly $100,000 for full compartmentation and sprinkler systems (Headwaters Economics). The upper end can rival rebuilding costs—and owners resist changes that compromise "authentic" aesthetics.

The Swiss resort of Crans-Montana learned this lesson fatally. On New Year's Eve, sparkler candles ignited a wooden ceiling at Le Constellation bar, killing 40 people and injuring 119 (Reuters, Jan 4). Local authorities later admitted the bar hadn't been inspected in five years—a lapse the mayor called a source of "bitter regret" (Euronews, Jan 6). While the fires share no direct link, they underscore a common alpine problem: heritage aesthetics without oversight.

What Safety Actually Looks Like

Courchevel's fire didn't become a mass-casualty event because detection, evacuation, and mutual aid worked. All 270–300 people got out safely; neighboring hotels quickly sheltered evacuees (France24, Jan 28). Four to six firefighters sustained minor injuries, but no one died (Libération, Jan 28).

The real story is systemic. When architectural aesthetics dictate construction and density accelerates spread, even £11,000-a-night rooms become vulnerable. As investigators work to identify the ignition source, the structural question remains: what changes when heritage meets fire code?

Retrofitting alpine luxury means hidden fire breaks, strategic sprinklers, and perhaps accepting that rustic charm needs a steel spine. The alternative is another night watching premium architecture become premium kindling—and the next time, mutual aid might not be enough.

Editorial Note: Confirmed facts as of publication—270–300 evacuated (Les Grandes Alpes and Hotel Le Lana) on January 28, 2026; fire originated in attic; 110+ firefighters responded; 4–6 minor firefighter injuries; fire circumscribed by afternoon January 28; Swiss Crans-Montana bar fire killed 40 on January 1, 2026. Unverified: allegations of Ukrainian ownership (single-source, no corroborating public records); specific guest/staff names; detailed renovation history; official cause determination pending gendarmerie investigation.