TL;DR: Cyprus's human-cat relationship began 9,500 years ago at Shillourokambos, the earliest known evidence of cat taming (Science, 2004). A 4th-century legend credits Saint Helen with importing snake-fighting cats, though historians find no proof. Today, an estimated one million strays—roughly one per resident—face welfare and ecological challenges. In October 2025, Cyprus tripled its sterilization budget to €300,000, but experts say only coordinated, year-round Trap-Neuter-Return can solve the crisis within 4–7 years (ABC News, Cyprus Mail, October 2025).

If you caught headlines about Cyprus recently, you saw the viral stat: as many stray cats as people. It's an easy shock. But the real story runs deeper—and stranger—than any clickbait suggests.

The Mediterranean island's modern cat crisis is tangled in a 9,500-year-old archaeological mystery, a medieval legend starring saints and serpents, and a cultural bond so strong it's both the problem and, possibly, the solution.

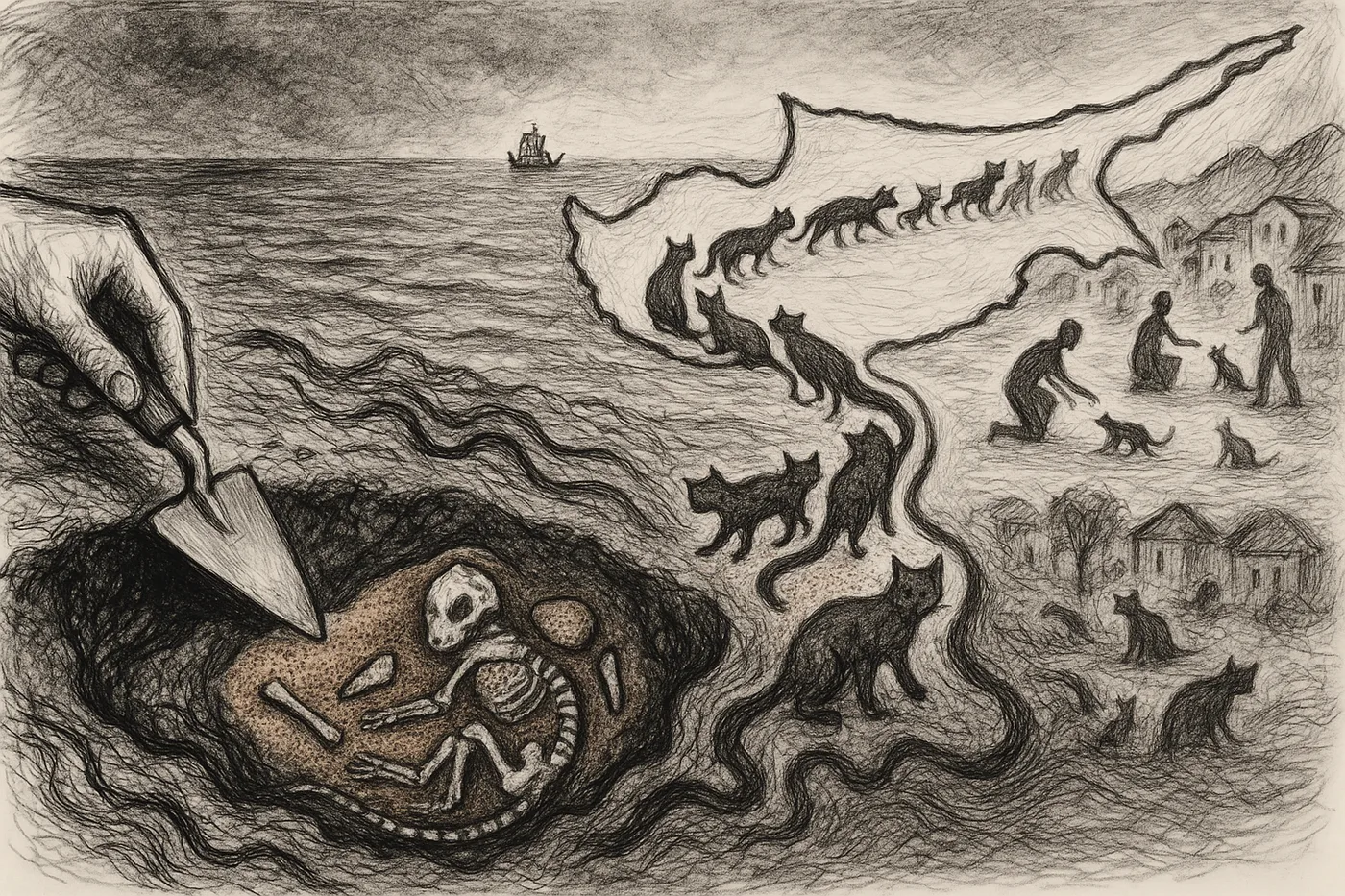

The First Purr? A 9,500-Year Partnership

Long before Egypt's pyramids rose, someone on Cyprus's southern coast was buried in a carefully prepared grave. Beside them: the complete skeleton of an eight-month-old cat, deliberately interred with shells, stone tools, and ochre.

This 2004 discovery at Shillourokambos, published in Science, dates to 7,500–7,000 BCE—the oldest known evidence of a human-cat relationship. Because cats aren't native to Cyprus, Neolithic settlers must have transported them by boat. Archaeologists Jean-Denis Vigne and Jean Guilaine concluded these weren't fully domesticated pets yet, but tamed wildcats in a partnership of mutual benefit.

As humans farmed, their grain stores attracted rodents. Rodents attracted cats. This symbiosis—pest control for proximity to food—predates Egyptian cat worship by thousands of years.

Bells for Snakes: The Saint Helen Legend

Archaeology gives us bones. Folklore gives us heroes.

A beloved medieval tale, first recorded centuries after the fact, credits Saint Helen—mother of Emperor Constantine—with turning Cyprus into the "island of cats." The story goes like this: in the 4th century AD, a 37-year drought left the island overrun with venomous snakes. Helen supposedly shipped hundreds of cats from Egypt or Palestine to the Monastery of St. Nicholas near Akrotiri.

The monastery allegedly used two bells—one to summon cats for meals, another to send them hunting. While Atlas Obscura and Wikipedia document the legend's persistence, no contemporary historical records verify it. The tale is exactly that: a tale. But it cemented the feline's heroic cultural status and explains why Cypriots remain so protective of their cats today.

Today's Numbers: One Million, More or Less

From medieval legend to modern reality, the numbers have exploded.

Officials estimate roughly one million stray and feral cats now roam Cyprus—about one per human resident, based on the Republic's population of approximately 1.2 million (ABC News, October 2025). Activists argue the true figure could be hundreds of thousands higher. During a September 2025 parliamentary session, Environment Commissioner Antonia Theodosiou acknowledged Cyprus may have the highest cat-to-human ratio globally.

The scale overwhelms informal caregiving. Authorities are requesting municipalities to map colony hotspots, but comprehensive population data remains elusive.

What this means: Without accurate counts, targeting sterilization efforts becomes guesswork.

When Compassion Collides With Ecology

An unmanaged cat population creates twin crises.

For native wildlife, cats are devastatingly efficient hunters. A 2023 Nature Communications synthesis documented 2,084 species in free-ranging cat diets worldwide, including 347 species of conservation concern. On a Mediterranean island like Cyprus, that means pressure on endemic birds and reptiles.

For the cats themselves, street life is brutal. Hunger, traffic injuries, fights, and disease are constant threats. Female cats are harder to trap, allowing breeding to continue unchecked. At €55 per female sterilization—rising to €120 for domesticated cats receiving full care—financial barriers have kept intervention modest.

Demetris Epaminondas, president of Cyprus's Veterinary Association, told AP that unchecked urban breeding and improved survival rates from public feeding have accelerated the crisis.

October 2025: Triple the Budget, But Is There a Plan?

For years, Cyprus's €100,000 annual sterilization budget funded only 2,000 procedures—what advocates called "a mere drop in the ocean."

On October 4, 2025—World Animal Day—the Ministry of Agriculture announced a shift. The government tripled cat sterilization funding to €300,000 as part of a €550,000 animal welfare package that also includes €100,000 for dog sterilization and €150,000 for a regional shelter in Paliometocho (Cyprus Mail, October 5, 2025).

Funds flow to municipalities, which contract private veterinarians for Trap-Neuter-Return (TNR) programs. The Veterinary Services acknowledged their "capabilities are lesser than the real need" and requested reports on high-concentration areas to redistribute resources more strategically.

The catch: Money without coordination achieves little.

The Volunteers Who Know the Territory

Real progress happens on the ground, led by exhausted volunteers and stretched-thin veterinarians.

Eleni Loizidou of Cat Alert in Nicosia told ABC News that her organization's recent roundup of 397 city-center cats felt like "a mere drop in the ocean." Female cats remain particularly difficult to trap, she noted—yet they're the key to slowing population growth.

Elias Demetriou, who runs Friends of Larnaca Cats, was blunt with reporters: tripling funds won't work unless officials recruit conservation groups who know how to locate and trap cats.

Behind the headlines, grassroots organizations like ResQstrays conduct year-round TNR at €30 per male, €60 per female, funded entirely by donations. Village volunteers with CopsCats describe their efforts as "a drop of water on a hot stone"—yet those drops add up. Cats In Need Cyprus and the Tala Cat Sanctuary near Paphos coordinate trapping, medical care, and managed colony oversight without government support.

These groups don't just love cats. They possess the institutional knowledge—which alleys harbor colonies, which females need trapping, which feeding schedules minimize conflict—that top-down policy can't replicate.

The Four-to-Seven-Year Solution

Experts agree: there's a path forward.

Epaminondas told reporters Cyprus could control its cat population in four to seven years with a unified sterilization plan. The requirements:

- Year-round, island-wide TNR prioritizing female sterilizations

- Expanded veterinary capacity through private clinics offering free-of-charge procedures with minimal bureaucracy

- Data infrastructure: population tracking, a smartphone app to map colonies (the Pancyprian Veterinary Association proposed this in 2023)

- Public education on responsible feeding at designated sites, microchipping, and registration

- Legalized sanctuaries for managed colonies with veterinary oversight

- Tourism-season planning to prevent feeding surges that spike kitten survival rates

Environment Commissioner Theodosiou stated her office is developing a long-term strategy to unite government agencies, veterinarians, and volunteers around mass sterilization and precise population counts (ABC News, October 2025).

The Pancyprian Veterinary Association suggested funding the program partly through corporate donations and public contributions, with the increased government budget acting as an incentive for private-sector participation (Cyprus Mail, October 2, 2025).

Bottom line: Technology + coordination + community expertise can bend the curve. But it requires sustained commitment beyond single-year budgets.

Ancient Affection, Modern Responsibility

The Cyprus cat story is about a bond that frayed under modern pressures.

The same compassion that led a Neolithic farmer to bury a feline companion 9,500 years ago—that inspired legends of snake-hunting heroes—still animates the volunteers leaving food bowls and the veterinarians working past midnight. The challenge now is channeling that deep cultural affection into coordinated, pragmatic action.

With tripled funding and growing political will, Cyprus has a chance to honor its ancient relationship by giving its cats a healthier, more manageable future. The tools exist. The expertise exists. What's needed is the discipline to scale what works—and the humility to let the people who know the cats lead the way.

Small acts, repeated at scale, can shift even a 9,500-year legacy toward something sustainable.