TLDR: This piece uses Nnena Kalu’s historic Turner Prize win to challenge how we define “serious” art and who gets to be called an artist. It shows how Kalu, an autistic artist with limited speech, builds intense, cocoon-like sculptures and rhythmic drawings through compulsive, bodily repetition—turning what looks like “nervous habit” into a fully realized visual language. The essay argues that her win exposes two quiet biases: an art world that equates verbal eloquence with artistic merit, and a double standard that celebrates studio assistants for famous neurotypical artists while questioning facilitators for learning-disabled ones. Framed by Bradford’s record-breaking exhibition, it positions supported studios like ActionSpace as vital but underfunded infrastructure—and ends by reframing our own fidgeting, pacing, and tactile rituals as legitimate starting points for creative work, not distractions from it.

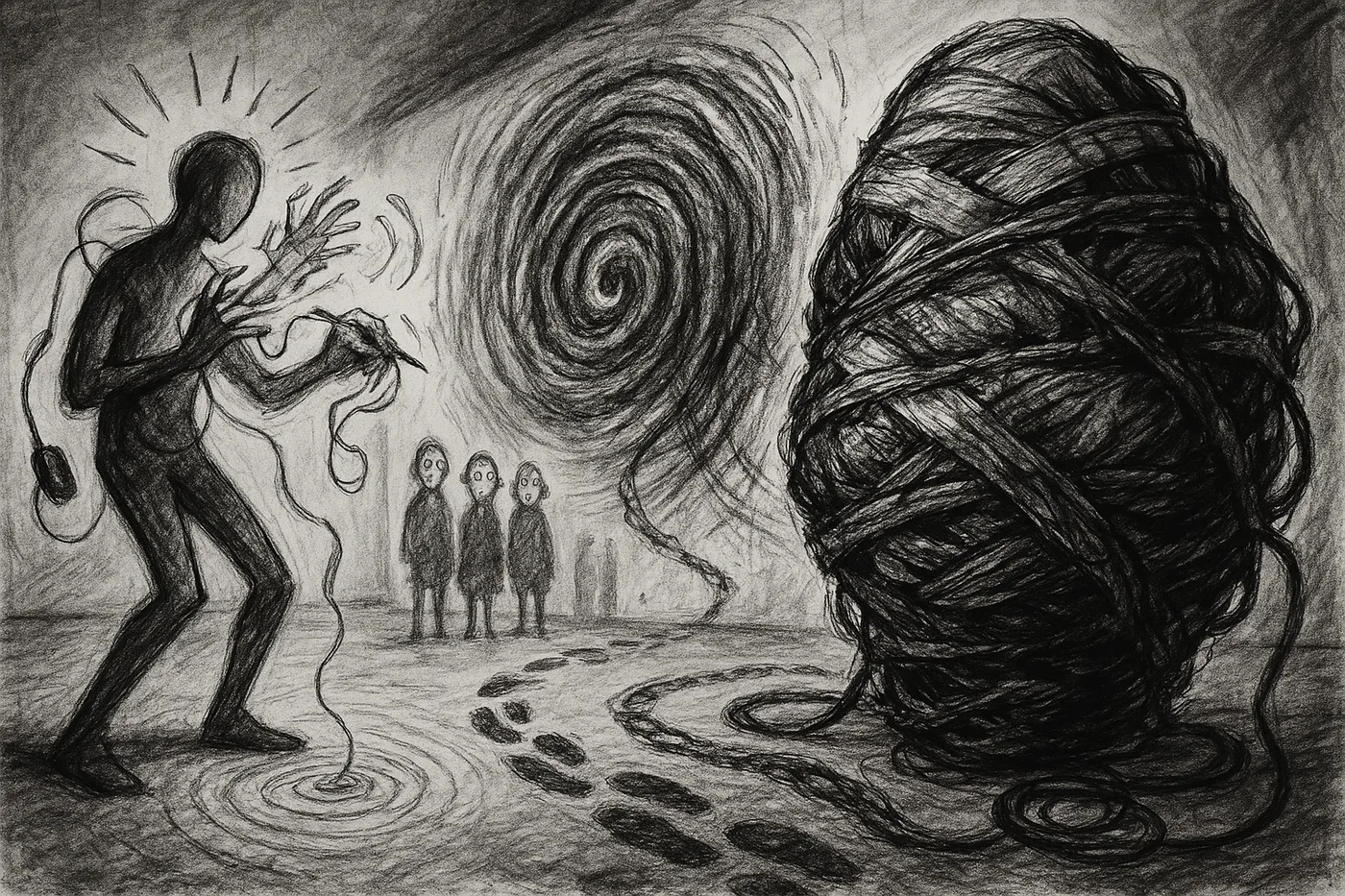

You know that feeling when you're trying to explain a complex idea but the words won't come? You start pacing the room. Tapping your pen on the desk. Doodling concentric circles in a notebook. Winding a headphone cable tightly around your finger. You're trying to physically work through a mental block.

Now imagine if that physical release wasn't just a nervous habit—it was a language in itself. Imagine if that rhythm was so precise, so intentional, and so visually commanding that it won the UK's most prestigious art award.

That's the energy behind Nnena Kalu's historic Turner Prize win. While headlines celebrate the firsts, the real story is about how a neurodivergent artist who barely speaks is forcing the art world to shut up and listen with its eyes.

The Context Worth Understanding

On December 9, 2025, Kalu was named winner of the Turner Prize at a ceremony in Bradford, broadcast by the BBC and presented by magician Steven Frayne. She took home £25,000, beating three talented runners-up who each received £10,000. The win marks a milestone: Kalu is the first autistic artist with limited verbal communication to claim the award.

The exhibition at Cartwright Hall Art Gallery—part of Bradford's 2025 UK City of Culture celebrations—has drawn over 34,000 visitors, proving public appetite for this work. But to understand why this matters, you need to look past the trophy and examine what she's actually making.

What You're Looking At

If you walked into the gallery expecting oil paintings or polite bronze statues, you'd be startled. Kalu's work is aggressive, tactile, massive.

Her signature cocoon-like sculptures are dense, chaotic bundles. She takes materials that most high-art purists would dismiss—textiles, paper, masking tape, old VHS tape—and compacts them into boulders or amorphous hanging forms. She binds them tight with layers of cellophane and tape until they look ready to burst with energy.

Her rhythmic drawings are equally physical. Vast, swirling vortexes created with repetitive gestures. She often works on them in pairs or trios, paper size determined by the reach of her own arms. This is art that doesn't just get looked at—it occupies a room like a living thing.

A Wordless Practice That's Still an Argument

Here's where the "wait, what?" factor kicks in. In an industry that loves over-intellectualizing everything, Kalu's creative process is refreshingly, radically biological.

Kalu doesn't write artist statements filled with jargon. She translates gesture into form. Her process is compulsive and repetitive—wrapping, binding, layering—extending her body's movements into physical space.

Think of kneading dough or knitting as a way to regulate your thoughts. Kalu scales that human impulse to architectural levels. As her team at ActionSpace describes it, she works to an innate rhythm, "like the sea coming in and out," often with loud disco music playing.

This challenges our definition of creative process. We typically think art starts with a concept that gets executed. For Kalu, the execution is the concept. The wrapping isn't the means to an end. The wrapping is the point.

What the Jury Revealed

The Turner Prize jury, chaired by Tate Britain Director Alex Farquharson, praised the work's "powerful presence" and "finesse of scale, composition, and color." They noted her "lively translation of expressive gesture into captivating abstract sculpture and drawing."

But there was also a telling emphasis: Kalu won on "merit alone."

That phrase reveals the art world's subconscious guilt. There's a deep-seated assumption in high culture that if a learning-disabled artist wins, it must be a sympathy vote or diversity play. By explicitly stating the art is good, the institution admits how high the barrier usually stands.

The jury validated what many have known for years: this isn't "outsider art" to be patronized. It's sophisticated spatial sculpture that holds its own against any theory-driven work.

The Ecosystem Nobody Mentions

Kalu didn't appear out of nowhere. She's been a practicing artist since the 1980s and has worked with ActionSpace—a supported studio for learning-disabled artists—since 1999.

At the ceremony, Charlotte Hollinshead, Kalu's studio manager and facilitator, spoke on her behalf. Her speech was a reality check. When Kalu started, her work was "not respected, not seen, and certainly wasn't regarded as cool." She spoke of a "stubborn glass ceiling" and decades of dismissal. "Nnena was ready years ago," Hollinshead said. "Everybody else wasn't."

This exposes a fascinating double standard. When neurotypical artists like Damien Hirst use teams of assistants to make their dot paintings, they're called genius managers. When neurodivergent artists use facilitators to help prep materials or manage studios, people question "authorship."

Kalu's win smashes that hypocrisy. The facilitators provide infrastructure so Kalu can do the work only she can do.

The Hidden Barrier on Trial

The most radical thing about Kalu's win? It challenges the "Instruction Manual" model of art.

We live in an era where art is often judged by how well artists can talk about it. Charm donors at galas, write clever 500-word essays for grants, explain your practice in terms that sound like postgraduate theory. It's a system rewarding verbal fluency and social masking, often at the expense of visual power.

Kalu's work refuses to play that game. It cannot be talked into being. It's experiential. It demands you shut off the part of your brain wanting verbal explanation and turn on the part understanding weight, tension, and rhythm.

Think about everyday parallels: workplaces and schools that confuse communication style with competence. Organizations that assume the person who speaks most confidently in meetings has the best ideas. Kalu's work exposes how much gatekeeping in "serious" art functions the exact same way.

Bradford and What Comes Next

It's fitting this happened in Bradford—the first time the Turner Prize has been hosted outside London in this context. Those massive visitor numbers suggest the general public doesn't share the art establishment's hang-ups about who gets to be an artist.

But a trophy doesn't fix systems overnight. Supported studios like ActionSpace are essential cultural infrastructure operating on precarious funding. Kalu's win is a massive symbolic victory. The real test will be whether the industry puts resources behind the next generation of neurodivergent artists.

Permission to Make Differently

Nnena Kalu's work offers more than a nice story about inclusion. It offers a permission slip.

Creativity isn't just about big ideas or perfect words. It's about the intelligence of the body. Next time you find yourself stuck, pacing the floor, twisting paper in your hands—don't stop. Don't treat it as a glitch. That rhythm is where work begins.

Kalu proved that if you follow that thread long enough and wrap it tight enough, it can change what we think art can be.

The Turner Prize 2025 exhibition continues at Cartwright Hall Art Gallery in Bradford until February 22, 2026. Admission is free.