TLDR: San Francisco just launched a first-of-its-kind lawsuit against 10 food and soda giants, arguing that ultra-processed foods are engineered to be addictive, deceptively marketed (especially to kids and low-income communities), and driving a tobacco-level public health crisis of obesity, diabetes, heart disease and more. Backed by emerging neuroscience and large-scale studies, the case claims many modern snacks and drinks are designed like slot machines—optimizing sugar, fat, salt, texture, and additives to hijack reward circuits so people unconsciously overeat, even when labels match for calories and nutrients. The lawsuit aims not just for marketing tweaks but for restrictions on targeting children, corrective education, and money to cover healthcare costs, and it sits inside a global shift toward sugar taxes, warning labels, and school-meal reforms. For individuals, the piece reframes late-night bingeing as a predictable response to engineered products rather than a personal failure, then offers practical ways to push back—spotting ultra-processed foods by their “chemistry-set” ingredients, making one small swap at a time, redesigning your environment, and treating your own cravings like an experiment—so you can regain more genuine choice in a food system built to keep you reaching into the bag.

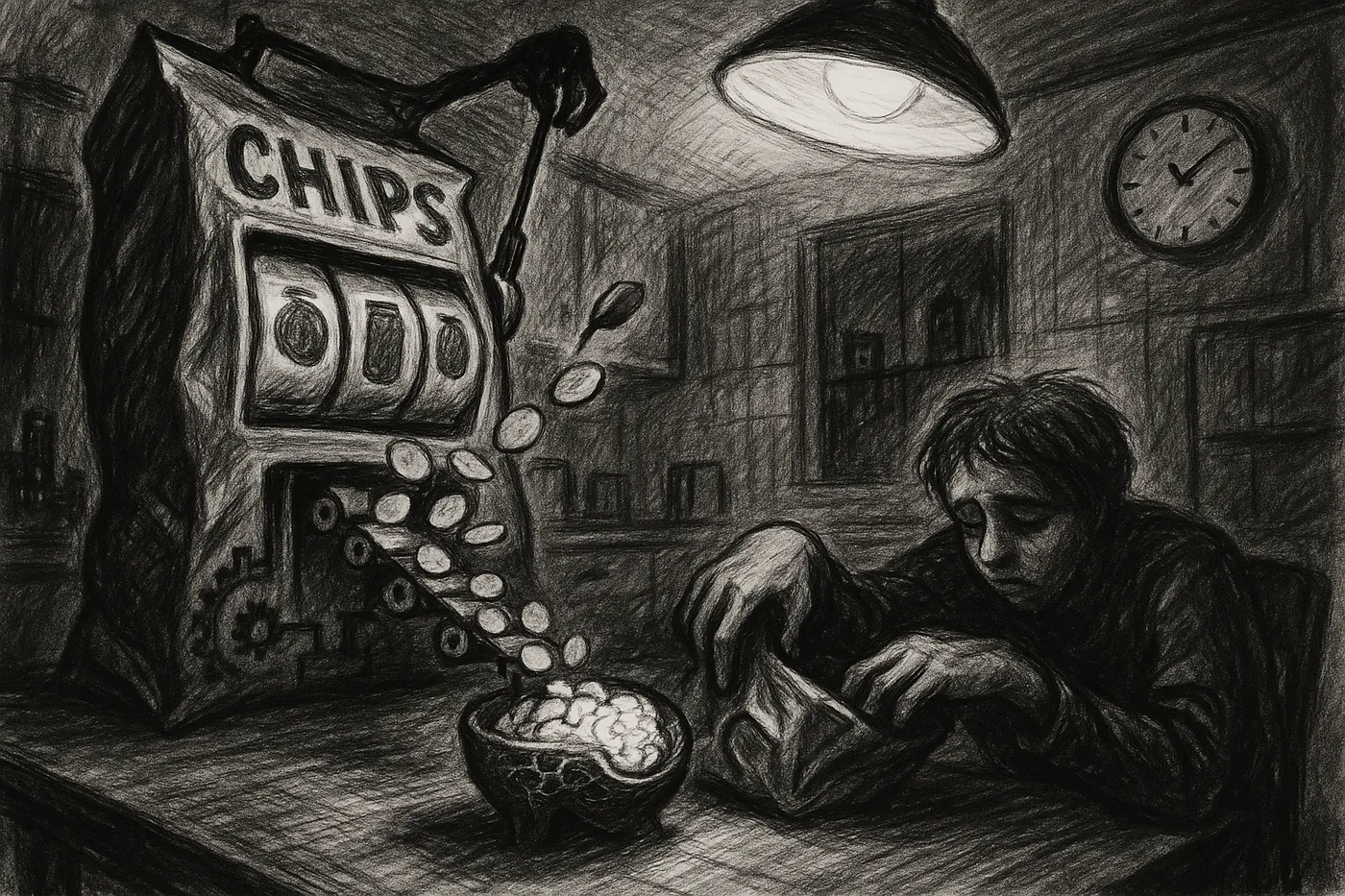

Picture this: It's 10 p.m., you're tired, and somehow you're at the bottom of a family-size bag of chips you absolutely did not intend to finish. You tell yourself it's willpower.

As of this week, San Francisco is arguing in court that moments like this aren't about willpower at all.

On December 2, City Attorney David Chiu filed the first government lawsuit of its kind against 10 ultra-processed food and soda giants—Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, Nestlé USA, Kraft Heinz, Mondelez, General Mills, Mars, Conagra, Post, and Kellogg's successors. The claim: these companies engineered ultra-processed foods to be addictive, deceptively marketed them, and helped fuel a public health crisis of obesity, diabetes, heart disease, fatty liver disease and some cancers.

Chiu is calling them the new Big Tobacco. And he's not just after ad tweaks—he wants injunctions on deceptive marketing, restrictions on advertising to kids, corrective education, and money back to cover healthcare costs for San Franciscans sickened by these products.

The wildest part? The case leans on a growing body of science that says many modern snacks and sodas work on your brain like a slot machine.

So: can your cereal really behave more like a casino than breakfast? And what do you do with that information without moving into a cabin and grinding your own flour?

What San Francisco Is Actually Suing Over

The lawsuit argues that ultra-processed foods now make up about 70% of the U.S. food supply. They're "formulations of chemically manipulated cheap ingredients with little if any whole food added," designed to "stimulate cravings and encourage overconsumption."

UPFs are linked to type 2 diabetes, fatty liver disease, heart disease, cancers and other chronic illnesses. Companies knew this, yet marketed aggressively—especially to children and vulnerable communities—violating California's Unfair Competition Law and public nuisance laws.

San Francisco has been here before. In 1998, the city secured a $539 million settlement from tobacco companies for deceptive practices and public health harms. Chiu is saying: "We've seen this movie. New product, same playbook."

But to understand why this isn't just rhetorical drama, we have to look at how these foods are built.

How Your Snacks Hijack Your Brain

Ultra-processed foods aren't just "foods with a label." They're industrial recipes built around ingredients you rarely use at home: high-fructose corn syrup, artificial sweeteners, emulsifiers, flavor enhancers, modified starches, synthetic colors.

They now provide about 55% of adult calories in the U.S., and nearly 62% for kids and teens.

Inside those recipes is an idea food scientist Howard Moskowitz helped popularize: the "bliss point." That's the precise combination of sugar, salt, fat and texture where a product tastes so good you don't get bored, but not so rich you want to stop. Think: "once you pop, you can't stop," but as a design brief.

Other tricks include vanishing caloric density—airy, melt-in-the-mouth snacks that disappear so fast your brain doesn't register fullness—and hyper-consistent flavor where every chip, every sip is identical and precisely tuned.

On the brain side, studies using brain scans and dopamine tracers show that high-sugar, high-fat UPFs can flood reward centers like the nucleus accumbens with dopamine in ways that resemble responses to nicotine, alcohol, or gambling.

Long-term, high-UPF diets have been linked to changes in reward circuitry and impulse control, smaller hippocampal volume, and higher risk of dementia and depression.

Psychologist Ashley Gearhardt, who studies ultra-processed food addiction, estimates that about 14% of adults and roughly 12% of kids meet criteria for "ultra-processed food addiction"—rates similar to addiction to alcohol or tobacco. Those numbers climb higher in people with obesity or food insecurity.

Is every brain wired this way? No. Some studies show very mixed dopamine responses. There's still no official "UPF addiction" diagnosis in psychiatry manuals.

But the pattern is hard to ignore: when you combine rapid hits of sugar and fat with engineered flavor and constant cues—ads, packaging, placement at checkout—you get behavior that looks like compulsion.

From Cigarettes to Cereal: The Tobacco Playbook

Here's where the "new tobacco" label goes from spicy metaphor to "wait, what?"

In the 1980s, tobacco giants like Philip Morris bought major food companies, including Kraft and General Foods. They brought deep expertise in designing products to deliver rapid pleasure, marketing to kids and vulnerable groups, and funding doubt whenever outsiders raised health concerns.

The San Francisco complaint cites a 1999 talk by Michael Mudd, a senior Kraft executive at the time, warning that ultra-processed foods were driving an estimated 300,000 premature deaths a year in the U.S. and up to $100 billion in costs—on track to rival tobacco's toll.

Two decades later, Lancet and BMJ umbrella reviews pulling together dozens of long-term studies find that high UPF intake is associated with roughly 32% higher risk of obesity, about 37% higher risk of type 2 diabetes, increased hypertension, heart disease, depression, and early death—at least 25 different adverse health outcomes overall.

Industry trade groups respond that there is "no agreed definition" of ultra-processed foods and that focusing on processing "misleads consumers." Food-science bodies critique the classification system and call for more nuanced frameworks.

Some of that scientific critique is valid. But if it's giving you déjà vu from the "we need more research" era of tobacco, you're not alone.

As one attorney helping San Francisco put it, "Tobacco has hijacked our food system for decades. The techniques they developed for selling cigarettes, they're using to sell ultra-processed foods to children."

Who Pays the Price?

On paper, this is a case caption in San Francisco Superior Court. On the ground, it's about whose bodies absorb the fallout.

Chiu's office points out that heart disease and diabetes are among San Francisco's leading causes of death, with diagnosis rates higher in minority and low-income communities. Cheap, aggressively marketed UPFs are often the most available and affordable options in those neighborhoods.

Imagine a parent in the Bayview or Tenderloin working two jobs. The corner store is packed with bright cereals, sodas, energy drinks, instant noodles, frozen snacks. The kids have seen these brands on YouTube, in games, on billboards. Whole-food options are more expensive, less convenient, or simply not nearby.

Gearhardt's research suggests food insecurity is linked to higher rates of ultra-processed food addiction symptoms. In some younger, lower-income groups, UPFs can make up 60-80% of total calories.

Multiply that dynamic across cities and countries, and you get what global experts are now calling a "chronic disease pandemic" driven in part by ultra-processed diets.

Is Ultra-Processed Food Really "The New Tobacco"?

Is a can of soda the same as a cigarette? No. But the comparison isn't random.

Where the analogy fits:

Companies have long-standing evidence that heavy UPF diets are harmful, but aggressively market anyway. Products are engineered for repeat use by exploiting brain reward systems. Lobbying and PR aim to muddy the waters and delay regulation. The health toll and healthcare costs are enormous and diffuse.

Where it differs:

Humans don't need cigarettes to live; they do need food. "Ultra-processed foods" is a very broad category; not all UPFs are nutritionally identical. Much of the evidence is observational; we're only beginning to understand precise mechanisms. There's active scientific debate over definitions and classification systems.

NIH researcher Kevin Hall's controlled trials add a crucial piece: when people are given two diets matched for calories, sugar, fat, and protein—but one is ultra-processed and one is minimally processed—they spontaneously eat about 500 extra calories a day on the UPF diet and gain weight. No one tells them to; the foods simply promote overconsumption.

So no, UPFs are not literally cigarettes. But from a "commercial determinants of health" perspective—how corporate strategies shape disease—they rhyme.

The Policy Ripple Effect

Globally, governments are starting to act. Over 100 countries have taxed sugar-sweetened beverages; meta-analyses suggest sales and intake drop around 15-18%.

Countries like Mexico, Chile, Colombia and Brazil have front-of-pack warning labels, restrictions on marketing unhealthy foods to kids, and school-meal standards that push for mostly whole or minimally processed foods.

A major Lancet series in 2025 called for integrating limits on UPFs directly into dietary guidelines, labeling "UPF markers" like artificial colors, flavors and sweeteners, and taxes and marketing restrictions to fund better access to real food.

In the U.S., California passed a first-in-the-nation law defining UPFs and planning to phase certain ones out of school meals by 2035. The American Heart Association has issued an advisory flagging UPFs as a heart health concern, especially in communities already facing inequities.

San Francisco's lawsuit slots into this bigger picture as a legal test case: can governments hold companies responsible not just for one misleading label, but for intentionally engineering and pushing a whole category of addictive, health-damaging products?

How to Outsmart Engineered Cravings

First, a reframe: if you feel "out of control" around certain snacks, that's not a personal failure. It is a sign that these products are doing what they were built to do.

Instead of shame, try curiosity. Treat your cravings like a science experiment where you are both subject and lead investigator.

Spot the ultra-processed culprits quickly

At the store or in your kitchen, flip a package and ask: Does the ingredient list run longer than 5-7 items? Do I see things I wouldn't cook with at home—emulsifiers, "artificial flavors," "colors," multiple sweeteners, modified starches? Is there very little actual food near the top of the list?

If yes, you're likely looking at an ultra-processed formulation. Turn it into a mini game: "Kitchen or chemistry set?"

Make tiny, realistic swaps

You don't have to go full organic homesteader. Try one swap at a time:

- Soda → sparkling water with lemon, lime, or a splash of 100% juice

- Flavored chips → air-popped or stovetop popcorn with oil and salt

- Candy-like breakfast cereal → oats with fruit and nuts, or a less processed muesli

- Frozen UPF dinners multiple nights a week → one night batch-cooking a simple chili, soup, or stir-fry you can reheat

Fiber and intact structure slow how quickly sugar and fat hit your bloodstream, which means a gentler dopamine response and less of that "slot machine" spike-and-crash.

Notice your triggers—and give your brain alternatives

Gearhardt and colleagues suggest asking: when do I reach for these foods most? Late at night? After stressful emails? While scrolling?

Experiment with other "hits" that soothe or stimulate: a quick walk, music, stretching, calling a friend, doing something creative with your hands for five minutes.

If you still choose the snack, that's okay. The point is to create a tiny gap between feeling and automatic eating.

Design your environment to work for you

Willpower is overrated; environment is powerful.

Keep the most "can't stop" foods off your most visible shelf; put fruit, nuts, or yogurt where you'll see them first. Prep a couple of simple things once or twice a week—cut veggies, cooked grains, beans, boiled eggs—so there's always something grab-and-go besides the bag of neon chips.

Controlled trials suggest that when people shift from UPF-heavy diets to minimally processed meals, their calorie intake drops by about 500 per day without trying. That's environment, not virtue.

What Now?

Next time you find yourself halfway through a bag of something before you've even decided you're hungry, remember: there is literally a city arguing in court that this isn't just "on you."

Big picture, we're living through a huge experiment where ultra-processed foods have quietly taken over most of our calories, and the scientific jury is coming back with a consistent message: this way of eating is hurting almost every major system in the body.

At the same time, cracks are forming. San Francisco is suing. Global experts are calling for warning labels, taxes, and marketing bans. School meal rules are changing. The idea that "food is just personal choice" is giving way to a more honest question: who built the choices?

You don't have to be perfect, or puritanical, or give up every comfort food. You can start much smaller:

- Pick one product in your kitchen this week and read the ingredients like a detective.

- Notice which foods feel most "slot machine-like" for you.

- Try one tiny swap or environment tweak and see how your body responds.

The science of how food interacts with your brain is still unfolding. Paying attention isn't about fear—it's about reclaiming freedom and pleasure in a system that hasn't always had your health in mind.

The snacks may be engineered. Your curiosity is not.