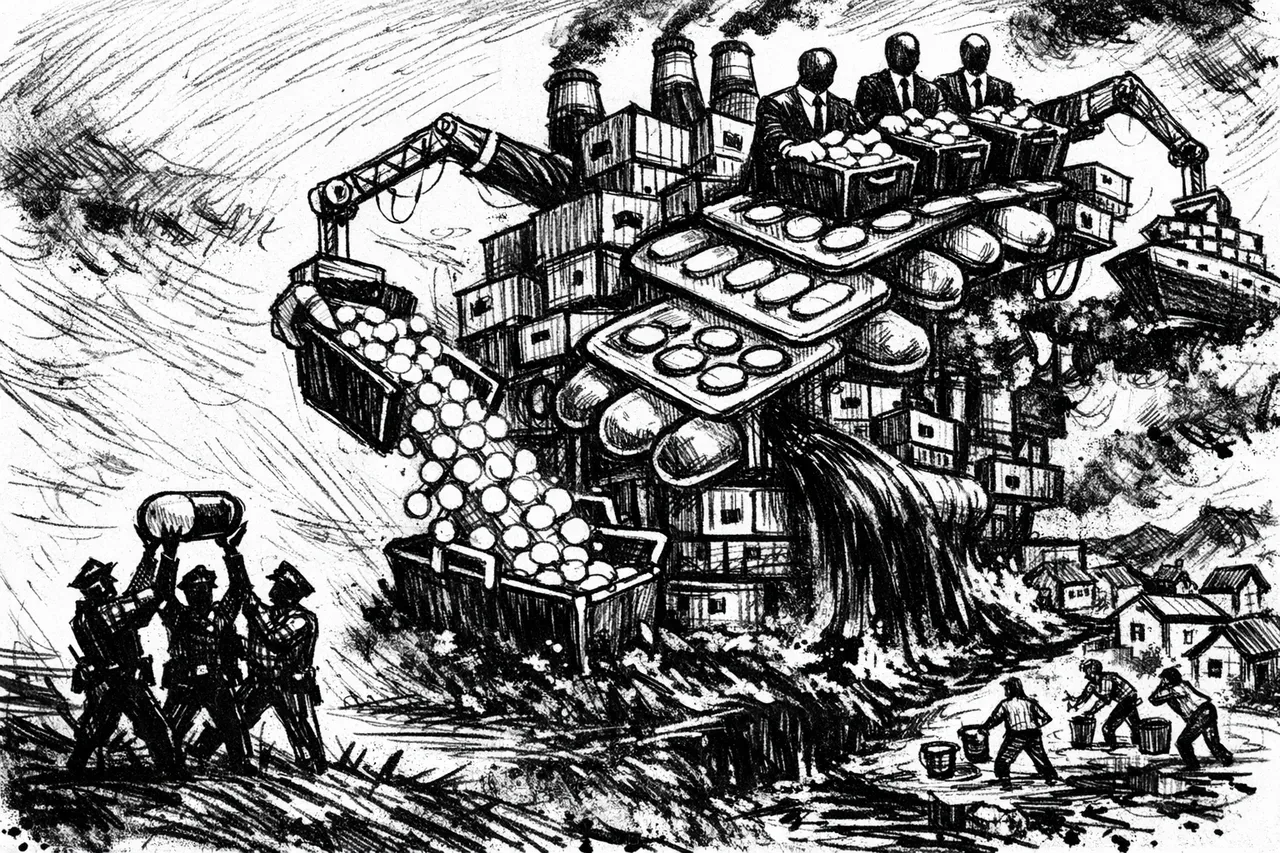

TLDR: Europol's bust of 24 industrial drug labs revealed a 30-to-1 profit enterprise that copied Big Pharma logistics: front companies imported Asian chemicals through legitimate trade, generating 120,000 liters of toxic waste that communities—not criminals—must pay to clean up.

Picture a warehouse in Poland. Drums of pharmaceutical-grade chemicals stacked floor to ceiling, each container labeled for legitimate medical use. Now picture those same chemicals repackaged, mislabeled, and shipped to hidden labs across Europe where they become MDMA, amphetamine, and synthetic cathinones.

That's not a street-corner operation. That's logistics.

On January 16, 2026, Europol coordinated raids across six countries, dismantling 24 industrial-scale drug laboratories. They seized over 1,000 tonnes of chemical precursors—enough to produce 300 tonnes of synthetic drugs—along with 120,000 liters of toxic waste, €500,000 in cash, and properties worth €2.5 million. Eighty-five people were arrested.

This isn't another bust recap. It's an exposé of an industrial underworld that copied Big Pharma's playbook: front companies, procurement specialists, distribution networks, and ruthless cost externalization. The system it reveals is stable, profitable, and built to last.

The Bust That Looks Like a Business

Operation Fabryka started in 2022 when Polish police noticed unusual chemical shipments arriving in Wrocław. By 2024, investigators had mapped a network importing pharmaceutical chemicals from China and India in quantities far exceeding any legitimate need.

The scheme was elegant. Seven legally registered Polish companies served as fronts, importing precursors with proper paperwork, then repackaging and mislabeling them for distribution to clandestine labs across the EU. Polish firms handled procurement and warehousing. Belgian and Dutch cells managed logistics, production, and money laundering.

Over 100 locations were searched—50 delivery sites, 16 storage facilities. Europol's Andy Kraag described it as targeting the industry "at its source." The drugs were just the final product of a much larger industrial enterprise.

The Profit Math

The numbers are absurd.

Polish police confirmed the network achieved a 30-to-1 return on investment. For every euro spent on production, they made thirty euros in profit. Kraag called these returns "considerable." Everyone else might call them astronomical.

Synthetics scale differently than plant-based drugs. No growing season. No crop failure. No dependence on agricultural land. Just manufacturing: inputs go in, outputs come out. Production ramps as long as you have precursors and lab space.

That 30x return explains the constant reinvestment. The network didn't just make drugs. It built industrial capacity designed for growth. Each shipment funded the next. Each lab refined its processes. The business functions mirror any legitimate corporation: procurement, quality control, distribution, finance.

The only difference is what they sold and who paid the hidden costs.

The Global Precursor Pipeline

The most modern part of this crime wasn't the chemistry. It was the logistics.

China and India dominate global chemical production. Their pharmaceutical and industrial sectors manufacture enormous volumes of legal precursors—substances that can also make illicit drugs. Criminal networks exploit this scale, placing orders that blend into legitimate trade flows.

The chemicals enter the EU through various ports with correct documentation for pharmaceutical use. Poland became the repackaging hub. Front companies received shipments, broke down bulk containers, relabeled them, and sent them to labs across Europe.

This camouflage was crucial. Every drum had paperwork. Every shipment had a plausible destination. The network operated inside legal trade infrastructure until the moment of final synthesis.

Regulators face a moving target. As authorities ban specific precursors, manufacturers shift to pre-precursors—slightly different chemicals that convert to the same end product in conversion labs. Each additional stage generates more waste and creates more regulatory gaps. Polish police noted they're "constantly updating the list of precursors entering the market," an admission that the rulebook always lags behind the chemistry.

The Toxic Balance Sheet

The seized 120,000 liters of toxic waste represents a fraction of what this network generated.

Kraag put it bluntly: "Today, it's profit for criminals. Tomorrow, it's pollution."

Synthetic drug production creates massive waste streams. For every kilogram of MDMA or amphetamine produced, manufacturers generate six to ten times that weight in toxic byproducts. Solvents, acids, contaminated residues. Criminals dump this waste on land, into streams, or down sewage systems.

The consequences are severe. Research documents sewage treatment plant failures, soil and river contamination, toxic vapors permeating buildings, and properties rendered uninhabitable. Cleanup requires specialized teams and massive expense—costs paid by communities, not the criminals who profited.

The environmental damage becomes a permanent externality, a hidden subsidy for the drug trade.

Why Networks Like This Persist

Operation Fabryka was genuinely massive. Kraag called it "by far the largest-ever operation we did against synthetic drug production." Investigators seized enough precursors to remove 300 tonnes of drugs from the market.

Yet Kraag also confirmed investigators are "continuing to pursue other networks believed to be operating across Europe."

The market adapts. High returns attract new entrants. Modular network structures mean knocking out one procurement cell or production lab doesn't collapse the entire system. It creates temporary supply gaps that other groups fill.

The taskforce launched at the end of 2024 reflects a strategic shift: target the supply chain, not just the end product. But supply chains are resilient. They reroute. They substitute chemicals. They fragment across more jurisdictions.

As long as demand exists and production yields 30x returns, someone will manage the risk.

The Uncomfortable Takeaway

Operation Fabryka exposed not a single criminal ring but an industrial model hiding inside legitimate commerce.

The profit math makes it inevitable. The global chemical trade makes it possible. The environmental devastation makes it catastrophic. And the network's persistence makes clear that busts alone won't solve the problem.

The uncomfortable truth: the most sophisticated part of this crime wasn't the chemistry. It was the logistics. The same global trade infrastructure that delivers life-saving medications also enables this rogue industry. Addressing it requires looking beyond law enforcement—upstream regulation of chemical flows, international cooperation on waste tracking, and serious accounting of environmental crimes.

The human creativity that built this system can also build better oversight. If we choose to.