TLDR: While headlines focus on its unique lemon shape, the real significance of exoplanet PSR J2322-2650b lies in an impossible carbon-dominated atmosphere that contradicts every existing model of planetary formation. This discovery forces a fundamental rethink of how worlds

You've probably seen the headlines: astronomers discover a lemon-shaped planet. Cue the viral tweets, the fruit comparisons, the inevitable puns. But here's what the breathless coverage misses—the shape of PSR J2322-2650b is the least strange thing about it.

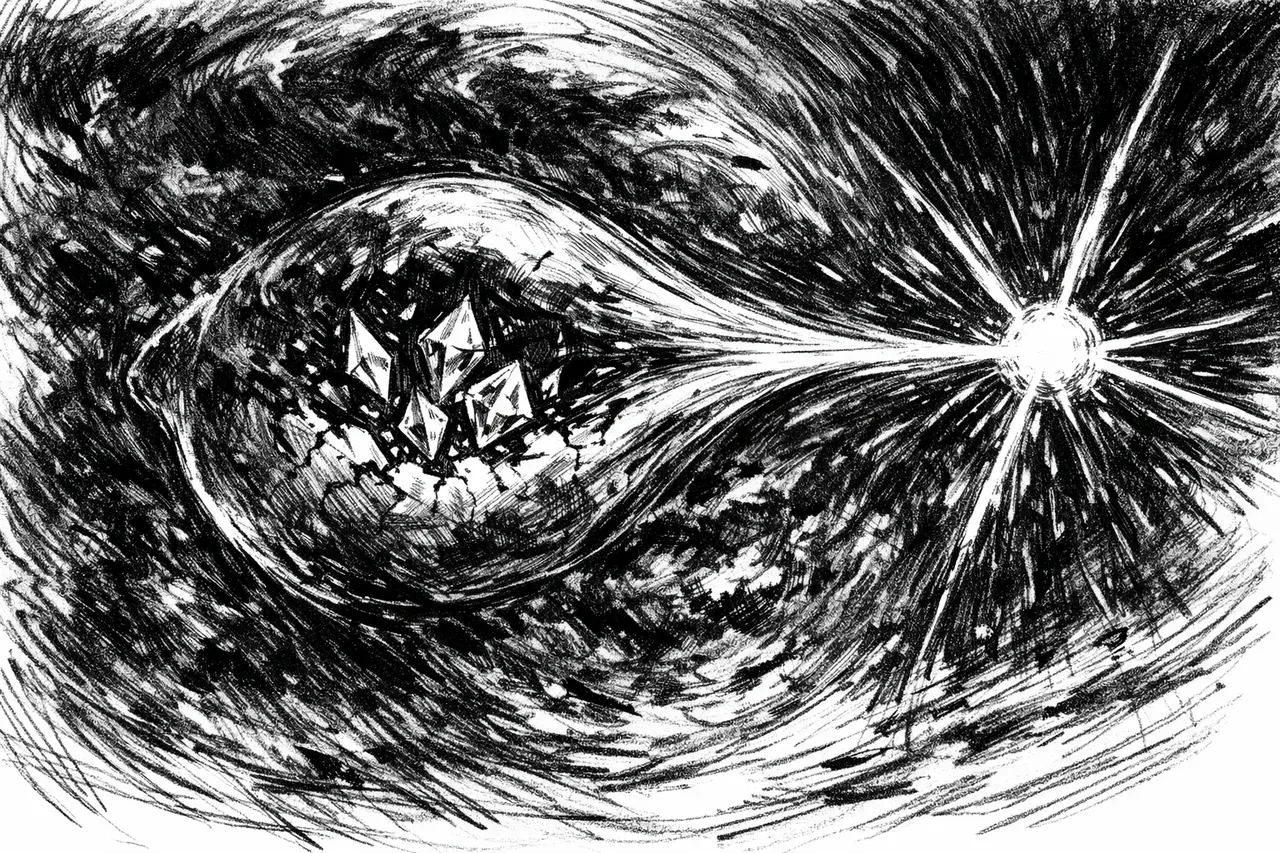

Strip away the geometry and what remains is a world that shouldn't exist according to every planetary formation model we have. This Jupiter-sized object orbits a rapidly spinning dead star at a distance that should have obliterated it long ago. Its atmosphere contains elements in ratios that defy conventional chemistry. And when the James Webb Space Telescope finally got a clear look at it in 2025, lead researchers had one collective response: "What the hell is this?"

PSR J2322-2650b isn't just weird. It's a fundamental challenge to how we understand planets form, survive, and evolve.

The Basics: A World in Hostile Territory

PSR J2322-2650b was first identified in 2017 through radio telescope observations, but it took JWST's infrared capabilities to reveal just how bizarre this world truly is. Located approximately 750 light-years away in the constellation Sculptor, the planet has a mass of about 0.8 times that of Jupiter but orbits a millisecond pulsar—the ultra-dense remnant of a massive star that exploded in a supernova.

The pulsar, PSR J2322-2650, packs the mass of our Sun into a sphere roughly the size of a city and spins approximately 300 times per second. The planet circles this cosmic lighthouse at just 1 million miles—barely 1 percent of Earth's distance from the Sun. At this proximity, a complete orbit takes only 7.8 hours.

The consequences are extreme. The dayside reaches temperatures of 3,700°F, while even the nightside never cools below 1,200°F. And the pulsar's intense gravity doesn't just hold the planet in place—it actively warps its shape.

Why "Lemon-Shaped" Actually Matters

The planet's distinctive oblong profile isn't a cosmetic quirk. It's evidence of gravitational violence in real time.

When an object orbits this close to such a massive companion, tidal forces—the difference in gravitational pull between the near side and far side—become extreme. Modeling of the planet's brightness variations throughout its orbit suggests PSR J2322-2650b is stretched approximately 38 percent wider along its equator than a perfect sphere would be. The pulsar's gravity is literally trying to tear it apart.

This permanent distortion indicates intense internal stress, disrupted heat distribution, and atmospheric dynamics unlike anything observed on more distant gas giants. The "lemon" isn't just a visual novelty—it's a record of survival under conditions that would destroy most worlds.

Black Widow Systems: Where Companions Go to Die

To understand why PSR J2322-2650b's existence is so puzzling, you need to understand the neighborhood it lives in. The planet orbits what astronomers call a "black widow-like" pulsar system—environments where companions typically don't survive.

Here's how these systems work: a pulsar spins up to incredible speeds by stealing material from a nearby companion star. Once the pulsar reaches millisecond periods, it begins generating intense winds of radiation that bombard and slowly strip away the companion. Over time, these systems usually end with a pulsar and a cloud of evaporated stellar material.

PSR J2322-2650b doesn't fit this pattern. It has the mass and density of a gas giant planet, yet it exists in a region where astronomical violence should have reduced it to nothing.

One leading explanation is that we're witnessing an object in the final stages of this stripping process—possibly what remains after losing up to 99.9 percent of its original mass. Under this scenario, PSR J2322-2650b might be the hollowed core of a former star that reached a stable configuration just before complete annihilation. But even this explanation struggles to account for what JWST discovered about its atmosphere.

The 2025 Discovery: An Atmosphere Unlike Any Other

Pulsars are notoriously difficult targets for atmospheric studies because their intense radiation overwhelms nearby objects. But PSR J2322-2650b had a hidden advantage: at infrared wavelengths, the pulsar is effectively invisible. This allowed JWST to isolate the planet's emission spectrum with unprecedented precision across its entire 7.8-hour orbit.

What the telescope revealed stunned the research team led by Michael Zhang of the University of Chicago and Peter Gao of the Carnegie Earth and Planets Laboratory.

Every previously studied exoplanet atmosphere contains some combination of water vapor, methane, carbon dioxide, or molecular hydrogen. PSR J2322-2650b has none of these. Instead, its atmosphere is dominated by helium and molecular carbon—specifically C₂ and C₃ molecules. Oxygen is undetectable. Nitrogen appears to be entirely absent.

The carbon-to-oxygen ratio exceeds 100 to 1. The carbon-to-nitrogen ratio tops 10,000 to 1. In almost every known astrophysical environment, carbon appears alongside oxygen. Finding a world where carbon utterly dominates is unprecedented.

"It's very hard to imagine how you get this extremely carbon-enriched composition," Zhang stated. "It seems to rule out every known formation mechanism."

High-Pressure Carbon Chemistry: From Soot to Diamonds

The planet's carbon-heavy composition creates conditions found nowhere else in the known universe. In the upper atmosphere, where temperatures soar and carbon molecules dominate, conditions favor the formation of carbon particulates—essentially soot clouds drifting through an alien sky. This gives the world what some researchers have informally dubbed its "Goth" aesthetic: dark, carbon-laden haze shrouding a world of extremes.

But the chemistry gets more exotic with depth.

As you descend into the planet's interior, pressure increases dramatically. Under sufficient pressure and the right temperature conditions, elemental carbon can transform from gaseous or particulate forms into crystalline structures. Deep within PSR J2322-2650b, carbon may condense into graphite or even diamond.

Roger Romani of Stanford University, an expert on black widow pulsar systems, suggests this as a plausible outcome: "As the companion cools down, the mixture of carbon and oxygen in the interior starts to crystallize." While direct confirmation remains impossible with current technology, the physics supports diamond formation as a likely consequence of the planet's extreme internal conditions.

The result is a world where soot rains from dark skies and diamonds may form in the crushing depths—a chemical environment that challenges basic assumptions about planetary composition.

Breaking Every Formation Model

PSR J2322-2650b's atmospheric composition isn't just unusual—it's incompatible with our understanding of how planets form.

Standard planet formation occurs in protoplanetary disks, where dust and gas coalesce over millions of years. In these environments, carbon is always accompanied by oxygen and nitrogen. The chemical abundances we observe throughout the universe consistently show these elements appearing together.

The black widow companion scenario offers an alternative: perhaps this is a stripped stellar core rather than a planet. But nuclear physics doesn't produce pure carbon-helium mixtures either. Stars fuse hydrogen into helium and produce carbon through nucleosynthesis, but they invariably generate oxygen and nitrogen through the same processes.

Neither planetary formation nor stellar evolution accounts for what JWST observed. Michael Zhang put it bluntly: "Did this thing form like a normal planet? No, because the composition is entirely different."

The planet exists in a categorical void. It's too dense and hot to be a traditional gas giant. Its composition is wrong for a stripped stellar core. It may represent "an entirely new type of object that we don't have a name for," as Zhang suggested—forcing astronomers to expand their framework for what's possible in the universe.

The Westward Wind Problem

As if the shape and chemistry weren't puzzling enough, the planet's atmospheric circulation defies expectations for tidally locked worlds.

Most hot Jupiter exoplanets—gas giants orbiting close to their stars—exhibit strong eastward winds driven by their rapid rotation and permanent day-night divisions. PSR J2322-2650b's atmosphere moves in the opposite direction, with high-speed westward winds dominating its circulation patterns.

This unexpected behavior likely results from the combination of extremely rapid rotation, intense external radiation, and the unusual atmospheric composition. But it adds another layer to a system that already challenges our models at every turn.

What Cosmic Impossibilities Tell Us

The real significance of PSR J2322-2650b isn't that it's shaped like a lemon or nicknamed "Goth." It's that this single object forces a reckoning with the limits of our knowledge.

When Peter Gao saw the first JWST data, his reaction wasn't rehearsed scientific detachment—it was genuine confusion. That honest uncertainty is what scientific discovery actually looks like. It's messy, surprising, and occasionally baffling. The researchers studying this world are asking fundamental questions they can't yet answer: How did this form? What other pathways to planetary evolution exist that we've overlooked? Are there more objects like this hiding in pulsar systems we assumed were sterile?

PSR J2322-2650b survived conditions that should have destroyed it. It formed through processes our models can't explain. It maintains an atmosphere that defies conventional chemistry. Whether it's the last remnant of a dying stellar companion or the first example of an entirely new class of objects, it proves the universe has more tricks up its sleeve than we imagined.

The lemon shape got our attention. The survival story, the impossible chemistry, and the collapse of our formation models—that's why it matters. And somewhere in the gap between what we observe and what we can explain lies the next breakthrough in understanding how worlds come to be.