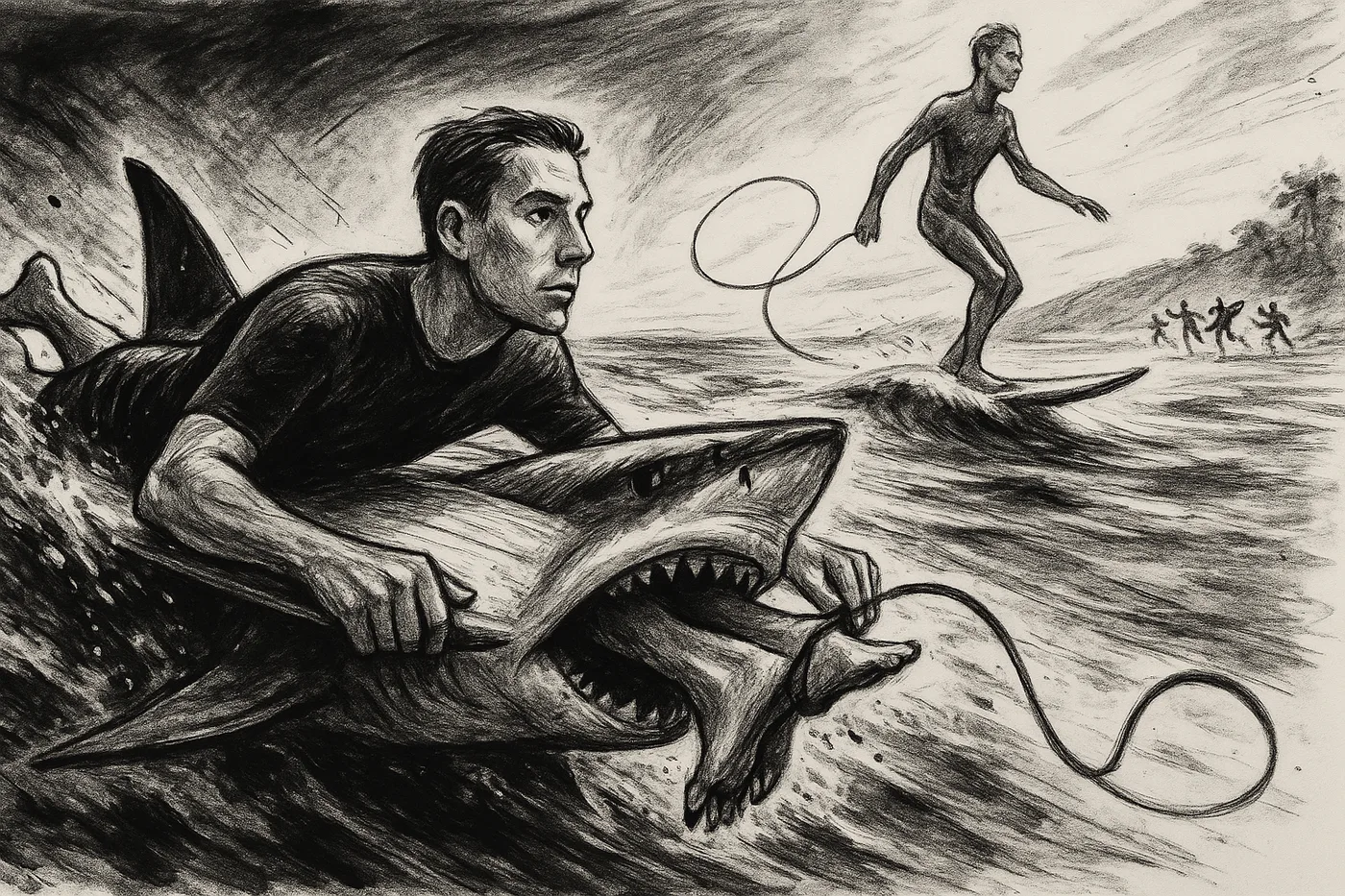

Picture this: It's a clear Friday afternoon in late October, and Cole Taschman is floating on his board off Bathtub Beach, feet dangling in the Atlantic. In less time than it takes to catch a breath, an eight-foot bull shark surfaces, clamps both feet in its jaws, and drags him under. When he emerges—screaming, bleeding, tendons severed—his first thought isn't why me? It's I need to get back out here.

Wait, what?

Cole Taschman is a shark attack survivor. Twice. Same beach. And somehow, that's not the most interesting part of his story. The real question lingers after the news vans leave and the 93 stitches start to heal: Why would anyone plan their surfing comeback before the hospital bills clear? The answer reveals something curious about human resilience, ocean safety myths, and what psychologists call post-traumatic growth.

The Repeat Bite Nobody Saw Coming

First time: 2013. Taschman was 16, surfing the "Stuart Rocks" break when a four-foot blacktip reef shark nipped his hand. Twelve stitches, one cast, back in the water. He called it "nothing compared to this."

Second time: October 25, 2025. A bull or tiger shark latched onto both feet simultaneously. The pain hit "like the sharpest knife you could ever imagine, times ten." He paddled himself to shore while girlfriend Ana filmed from the sand. Friends Hunter Roland and Zach Bucolo sprinted over, used surfboard leashes as tourniquets, loaded him into a truck, and drove him to the hospital—arriving faster than any ambulance could reach the remote beach. Taschman blacked out from pain during the ride.

The damage: three severed tendons, near-amputation of both feet, multiple surgeries, four hospital days, 10 staples, and no health insurance. The community response was immediate—Ohana Surf Shop launched fundraising raffles, a GoFundMe covered lost charter-captain income. But while doctors stitched him back together, Taschman was already making plans: "I will be surfing again. I definitely will."

Crunching the Odds: Why This Changes Nothing

The math is wild. In 2024, the International Shark Attack File confirmed just 47 unprovoked bites worldwide—down from a 10-year average of 70. Florida led the U.S. with 14 cases. Surfers account for 34% of incidents simply because they spend more time in the water than anyone else. The chance of being bitten at all? Less than 1 in 3.7 million per beach visit. Getting bitten twice at the same location over a decade? Statisticians call that a rounding error inside a rounding error.

You're more likely to be struck by lightning. Or injured getting out of your car.

Sharks aren't hunting humans—they're responding to splashing silhouettes that resemble injured prey. Most encounters last seconds. Ninety-six percent are non-fatal. Taschman's case isn't proof of hidden danger. It's proof of how vanishingly rare these events truly are, despite what every Shark Week marathon wants you to believe.

Inside His Head: Resilience, Flow, and Why He Goes Back

This isn't recklessness. It's love. Taschman describes the ocean as family, using the Hawaiian term "Ohana" to explain his commitment. "No one gets left behind," he says, and that includes himself.

Psychologists call this post-traumatic growth: trauma becoming a catalyst for deeper appreciation and purpose. For extreme-sport athletes, there's also the "flow state"—that immersive zone where focus narrows and the brain's reward centers ignite. Adrenaline isn't just a rush; it's confirmation of being fully alive.

The distinction matters: healthy obsession chases meaning. Compulsion chases chaos. Taschman's return isn't about courting danger. It's about reclaiming the place where he feels most himself.

Surfers develop what researchers call "ocean literacy"—practical, respectful understanding of marine risks. Dawn and dusk are shark prime time. Murky water where baitfish school raises risk. Surfing in groups and minimizing splashing shift the odds in your favor. Taschman's friends didn't panic because they'd rehearsed this scenario mentally a thousand times. When the moment came, they executed.

Ohana in Real Time: When Community Becomes the Safety Net

The tourniquets that saved Taschman's life weren't flukes—they were improvised from equipment every surfer carries. The fundraising covering his rent isn't charity; it's mutual aid from a community operating like extended family. Ohana Surf Shop didn't just post a link; they organized raffles for custom boards and fishing charters, turning crisis into collective action.

This network effect is the hidden architecture of resilience. When you're a 28-year-old Florida surfer without insurance, a shark attack threatens more than your body—it threatens your livelihood. But Taschman's community absorbed the shock. Friends drove him to the hospital. His girlfriend coordinated care. Local businesses fundraised. Strangers contributed. The result? He can focus on healing instead of bankruptcy.

There's something radical here. In an era of algorithmic isolation and institutional failure, a group of Floridians with surfboards built a safety net that actually catches people.

Myths, Murky Water, and the Real Safety Playbook

Let's clear the noise.

Myth: Sharks target humans.

Reality: They mistake us for prey. Most "attacks" are investigatory.

Myth: Shiny jewelry attracts sharks.

Reality: It might mimic fish scales, but baitfish schools are far bigger attractants.

Myth: There are "safe" times to surf.

Reality: Risk rises at dawn, dusk, and in murky water—like Bathtub Beach that day—but no time is zero-risk.

The International Shark Attack File offers practical, non-alarmist guidance: Stay in groups (sharks prefer solitary targets). Don't wander far from shore (isolation increases vulnerability). Avoid excessive splashing (mimics distressed prey). Respect baitfish—if you see birds diving and fish boiling, paddle elsewhere.

New technology emerges too: bite-resistant wetsuits, personal deterrents, drone surveillance. These aren't panic purchases. They're tools that restore control. For Taschman, control means returning on his own terms—from informed respect, not denial.

What This Story Reveals About Us

Taschman's planned comeback rebuts the culture of fear that sells news cycles and Shark Week marathons. Viral headlines want you to see a victim. He wants you to see a surfer. We're conditioned to treat trauma as a full stop, but his story argues for a comma—or an exclamation point.

When we reduce shark attacks to horror movies, we miss deeper lessons about risk, community, and purpose. Taschman isn't special because he got bitten twice. He's special because he refuses to let that define him. His curiosity about the ocean survived its greatest test, inviting us to ask: What are we so afraid of that we'd stop doing what we love?

The Wave He's Still Chasing

Cole Taschman will surf again. Not because he's fearless, but because he's fear-wise. He knows the odds, respects the ocean, trusts his community, and chooses meaning over safety theater.

So the next time you see a shark headline, pause. Ask what the data says. Ask what the survivor wants. And ask yourself what you'd chase if you weren't afraid of getting bitten. The ocean's been here for billions of years. It's not out to get us. But it will test us. How we respond—that's the only statistic that counts.