TLDR: A pod of orcas in Mexico’s Gulf of California has turned great-white hunting into a master class: they flip juvenile sharks upside-down to trigger paralysis, then delicately excise the calorie-dense liver and share it around—behavior documented 2020-2022 that reveals cultural innovation, climate-driven prey shifts, and the unsettling speed at which ocean ecosystems are rewriting their own rulebooks.

Did that orca just flip a great white shark like it was rehearsing for marine mammal Cirque du Soleil?

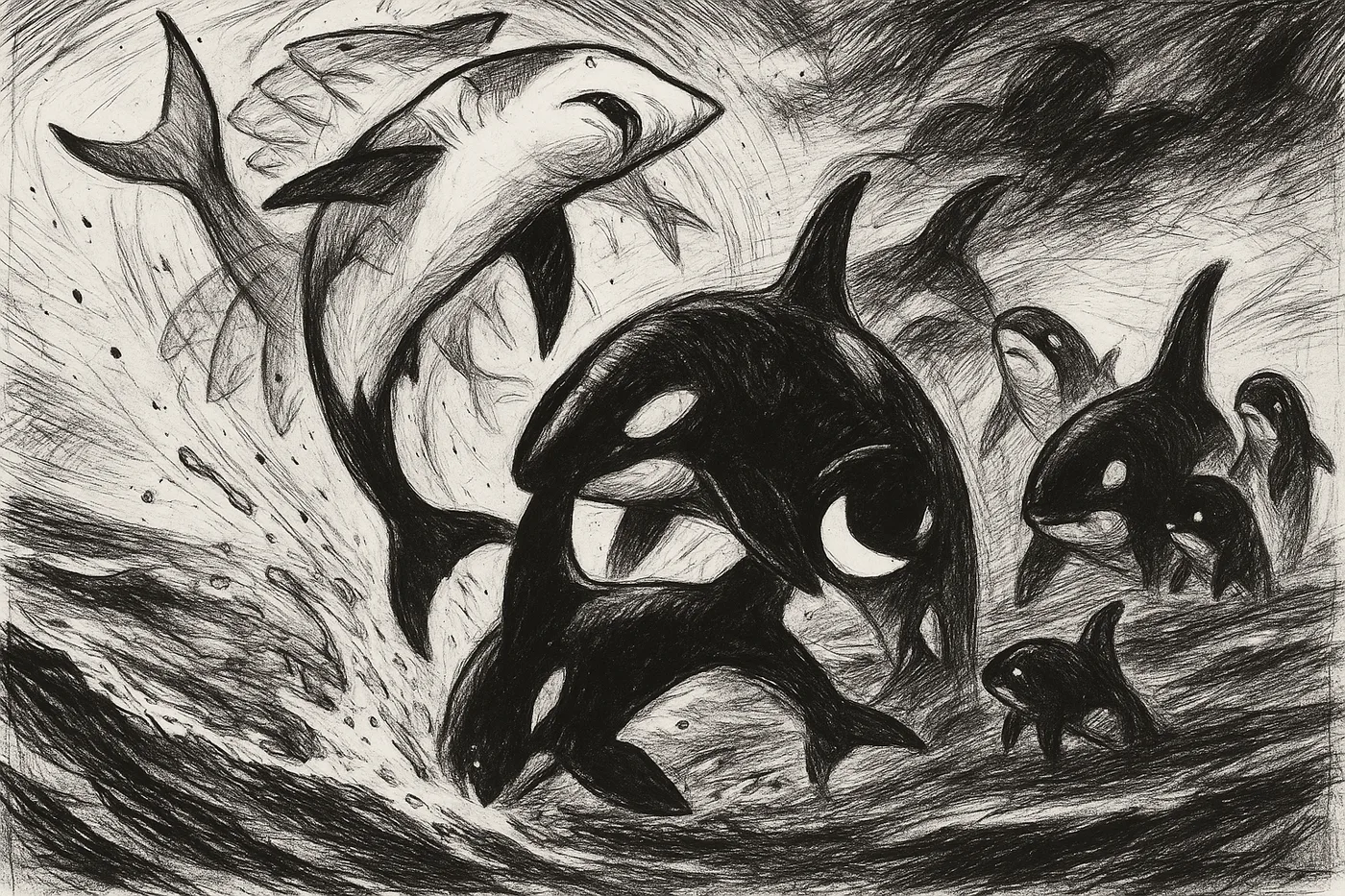

In the Gulf of California, a pod of orcas has perfected something extraordinary: they paralyze juvenile great white sharks by flipping them upside down, triggering a reflexive shutdown scientists call tonic immobility. Once the shark enters this temporary paralysis, the orcas surgically extract its nutrient-rich liver and pass it around like protein-packed tapas.

New research published in 2025 documents this technique happening repeatedly between 2020 and 2022 in Cabo Pulmo National Park, a protected marine area in Baja California Sur, Mexico. This isn't sensationalized predator drama. It's a window into animal intelligence, cultural innovation, and how ocean life adapts to a warming world faster than most of us realize.

The Precision Behind The Flip

Five orcas locate a juvenile great white roughly 2.5 meters long—essentially a teenage shark still figuring out how apex predation works. Working in coordinated formation, they drive the shark to the surface, then flip it onto its back using their rostrums. The moment the shark's spatial awareness gets disrupted, paralysis kicks in. While the shark lies immobilized, the orcas access its liver and share it among pod members, including calves.

This isn't brute force. It's learned precision that requires split-second timing and communication. Why risk injury from a struggling shark when you can induce suspended animation and dine risk-free?

The juveniles make ideal targets because of their inexperience. Adult great whites evacuate entire regions for months when hunting orcas appear. But younger sharks? Researchers still don't know whether anti-predator responses are instinctual or socially learned. Either way, these juveniles haven't gotten the memo. They're vulnerable, and Moctezuma’s pod has noticed.

Meet The Engineers Of Shark-Flip Culture

Moctezuma's pod functions like a specialized hunting guild with multi-generational expertise. Photo-identification reveals familiar faces: Moctezuma, the adult male first documented in 1992; Quetzalli, marked by a distinctive dorsal notch; Waay and Niich, identified by unique fin shapes. Since 2018, researchers have tracked these same individuals hunting Munk's pygmy devil rays, bull sharks, and whale sharks.

What sets this pod apart is dietary specialization. While some orca populations focus on fish and others on marine mammals, Moctezuma's crew developed expertise in elasmobranchs—sharks and rays. Each prey type gets custom tactics. Rays get tail slaps. Whale sharks get pelvic strikes that cause exsanguination. Juvenile great whites get the precision flip.

Cultural transmission happens in real-time. Calves observe. Juveniles practice under supervision. Successful techniques get refined and passed down. When the liver gets shared, it's not just nutrition—it's social bonding and knowledge transfer. Other orca groups in the region haven't adopted these tactics, suggesting innovation arises from specific ecological opportunities combined with social learning capacity.

This is orca culture, not genetic programming.

Climate Changed The Guest List

Ocean warming and El Niño cycles appear to be shifting great white nursery zones northward. Juveniles that would typically develop in southern California or Baja waters are increasingly showing up in the Gulf of California—right where Moctezuma's pod hunts.

The mechanism seems straightforward: warming waters alter where young sharks find preferred temperatures and food. As they move into unfamiliar territories, they encounter predators they've never faced before. Naive juveniles become easier prey than experienced adults.

But researchers emphasize caution. These are observations from a few years, not decades of established patterns. The data shows correlation between warming and shark migration, but ecosystem dynamics remain complex and incompletely understood. The Gulf is becoming a real-time laboratory for watching novel predator-prey relationships form—though the final exam results won't come in for years.

When Apex Predators Hunt Apex Predators

In South Africa, orca predation on great whites triggered mass shark evacuations, disrupted tourism economies, and sparked scientific debates about ecosystem stability. Could the Gulf see something similar?

Potentially, but the context differs. South African cases involved adult sharks and caused rapid behavioral shifts across regional populations. In the Gulf, pressure falls on juveniles, which could affect recruitment—the number of young sharks surviving to reproduce. Remove enough juveniles before they reach adulthood, and populations decline. That cascades through food webs in unpredictable ways.

Cabo Pulmo's marine protected status complicates predictions. The park's healthy ecosystem attracts both prey and predators. Researchers note that long-term monitoring remains limited. Compelling snapshots from 2020–2025 exist, but understanding whether this represents temporary adaptation or permanent shift requires sustained observation.

The ecosystem ripples are plausible. Definitive conclusions? Premature.

Why Shark Livers Beat The Standard Menu

Most people picture orcas hunting seals—dramatic beach attacks, wave-washing, coordinated harassment. Those tactics emphasize power and persistence. The shark-flip is different. It's surgical, requiring understanding of shark physiology and exploitation of a specific neurological vulnerability.

Why develop such specialization? Energy economics. A great white's liver comprises up to a third of its body weight, packed with lipids that deliver more calories per bite than most prey. For a pod that shares extensively, including with growing calves, that's high-value nutrition worth perfecting.

This versatility showcases what researchers call cognitive complexity. Orcas aren't just strong—they're adaptable problem-solvers. When environments change, they improvise. New prey appears? Invent new techniques. Old prey disappears? Adjust the strategy. It's the difference between following a recipe and cooking with whatever ingredients the ocean provides.

The Questions That Keep Scientists Up At Night

Will other Gulf orca pods adopt these tactics, or will this remain Moctezuma's exclusive innovation? How quickly can juvenile great whites learn avoidance, and will that knowledge spread culturally among shark populations? What monitoring systems can track these interactions without disturbing them?

Community science plays a surprising role. Many observations came from tourism operators and citizens who happened to have cameras ready. That creates participation opportunities but highlights gaps in systematic data collection. Sustained funding and respectful observation protocols remain essential.

Here's the most intriguing question: What happens if climate change fundamentally alters the Gulf's ecosystem in ways that make shark hunting unviable? Moctezuma's pod has acquired specialized knowledge through patient cultural transmission. That expertise could become obsolete overnight. Animal culture, like human culture, exists in fragile relationship with its environment.

The Ocean's Improvisation Never Stops

Watching another species innovate in real-time is humbling. Moctezuma's pod isn't just surviving—they're teaching, learning, and adapting with sophistication that challenges our definitions of intelligence. They're responding to the world we're reshaping, and they're doing it with creativity and cooperation.

This story rewards curiosity without demanding simple answers. It invites closer attention to complexity beneath the waves: cultural transmission, ecological negotiations, delicate balances sustaining marine life. The shock isn't just a flipped shark—it's recognizing the ocean constantly surprises us when we actually pay attention.

Every time we examine how other animals navigate change, we improve our own navigation skills. Orcas demonstrate what's possible when intelligence meets necessity. Our responsibility is ensuring they still have an ocean where that ingenuity can thrive—where juvenile sharks can learn, where cultural knowledge can transfer, where adaptation remains possible.

What aspects of animal intelligence surprise you most? Does knowing orcas have hunting cultures change how you think about ocean conservation? Share your thoughts below and let's keep this conversation swimming.